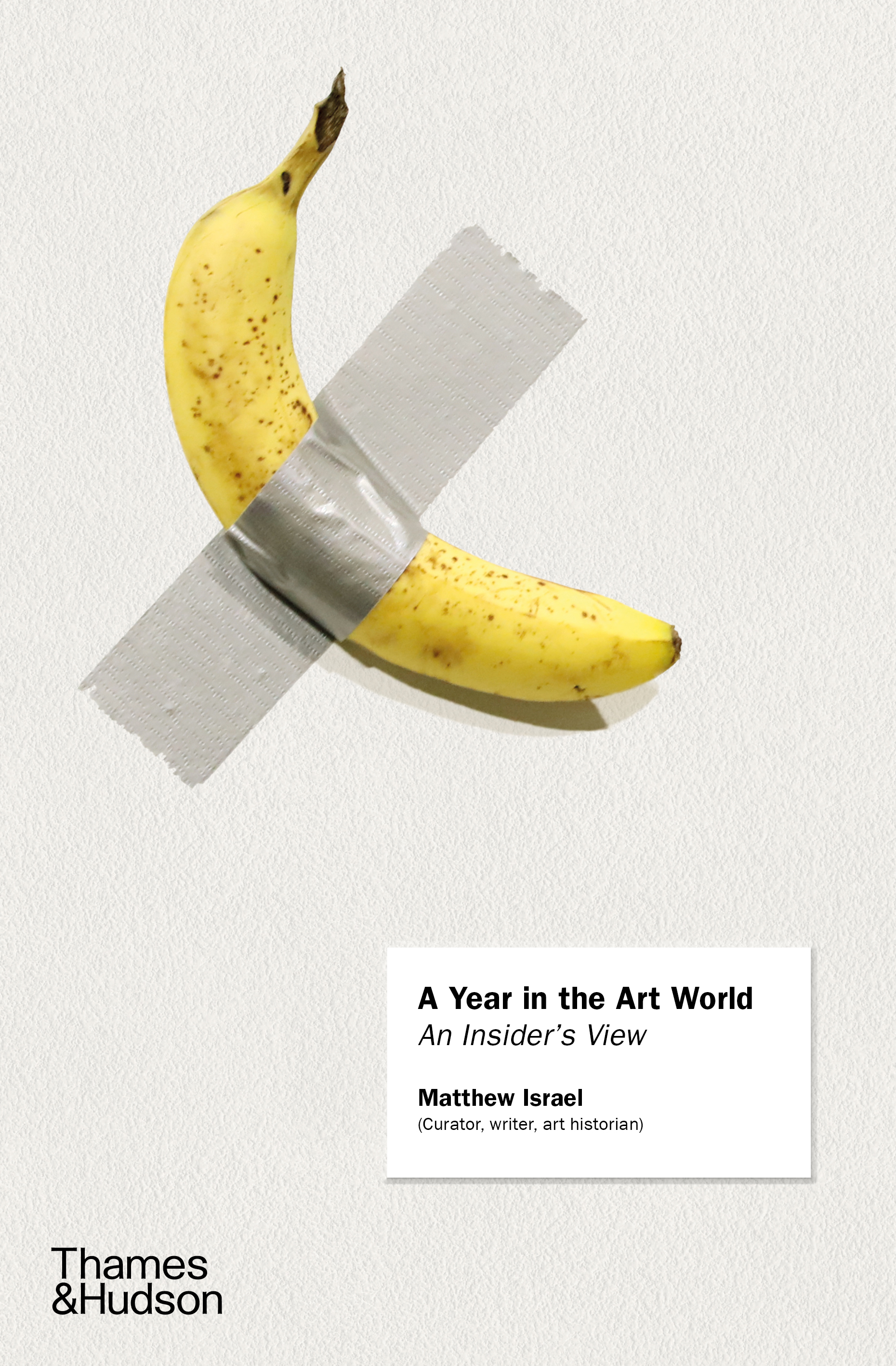

For his new book A Year in the Art World: An Insider's View (out September 15 from Thames & Hudson), Artful's Chief Curator Matthew Israel traveled widely in search of the experts who keep the vast machinery of the contemporary art world humming. He spoke with leading artists, curators, advisors, auction house specialists, and museum directors, not to mention many people in more behind-the-scenes but vital roles such as conservation and fabrication.

Because his book was written before the pandemic took hold, it reflects an art world in constant motion. But its candid, nuanced descriptions of different art careers, and its broader look at what it means to work in this industry, still apply to our homebound present. There's even a hint of the future, as Israel—who spent many years as the Head Curator for the online art platform Artsy—seeks out the visionaries who are shaping virtual art experiences.

Below is Artful Magazine's exclusive excerpt of A Year in the Art World, focusing on the Virtual Reality company Acute Art.

I'm falling.

I've been in this state for about fifteen minutes, but it feels like five. I've fallen into an endless hole, and I am slowly descending down into it through a series of dark-red, labyrinthine tunnels. At times they feel like caves. At other times, I feel like I am inside someone's body. There are bright lights surrounding me and at certain moments I see fluttering marks to the left and right of me. There is also music accompanying this descent. Then, suddenly, it ends. I feel bodies moving around me. "Is this done?" I ask.

I hear "Yes," and then I am helped with the process of taking off the device attached to my face: an HTC Vive headset, used for VR films. My eyes refocus on the carpeted floor, which has barriers indicated on it, showing where I should move and not move. I look at the computer rig in front of me. It looks complicated; not really something that could be set up in someone's home.

And then I look up. I see the staff of the London-based organization Acute Art looking back at me with somewhat inquisitive faces. They seem to be half interested in my reaction and half preoccupied with their other responsibilities of the day. The artwork I've just experienced is called Into Yourself, Fall and it was created with Acute Art in 2018 by Anish Kapoor, the British artist internationally known for his monumental sculptural works.

Acute Art is, as I write this, the most notable thing happening in VR for the art world, and it represents a sizeable shift in how the art world relates to VR and AR technologies. It is a company that doesn't look to these technologies to better represent artworks that have already been created in real life, but instead seeks to produce digitally immersive works which, most of the time, have no real-life component.

Acute Art was founded by the Swedish art collector Gerard De Geer and his son, Jacob De Geer. It is housed in a sparsely decorated, cream-colored office in Somerset House, home of the Courtauld Institute and museum, and it overlooks Waterloo Bridge.1 The company recently caught my attention because it had attracted a significant art world talent: Daniel Birnbaum. Birnbaum is one of the art world's most respected curators, and he left a prestigious post as the director of Stockholm's Moderna Museet to take on the role of director at Acute Art. The move was quite unexpected, as online projects – even if progressive – are still not considered elite in the art world, and Birnbaum has an impressive pedigree. He was head of the German art academy Städelschule and its associated exhibition space, Portikus, before taking on his role at the Moderna Museet; he was also the curator of the Venice Biennale in 2009, and is a contributing editor for Artforum.

While Acute Art is only a few years old and currently consists of an eight-person team supplemented by various freelancers, it has already undertaken projects with major artists: Anish Kapoor, Jeff Koons, Christo, Olafur Eliasson, Marina Abramović, Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg, and Antony Gormley. Birnbaum joined the team primarily to lead Acute Art's efforts to lure in other talented artists to work with. Thus far he has found the opportunity to be liberating, particularly in comparison to his past administrative and fundraising work in a museum. He recently explained in an interview, "For me, it's a move back to where I once began, which is being close to artists." He is excited to focus on questions like "What will artists do with these technologies? What can they do? What are their dreams?" He's also interested in what such technologies might mean for making art more accessible. He explains, "Ideally, digital works will be accessible in the suburbs of Lagos or outside of Zagreb. You won't have to go to Paris to see them. It's not about mass distribution, it's about omnipresence. This could really be art for all."2

While Acute Art is a for-profit company, they seem to have the funding and investment right now to not have to turn a profit anytime soon. Irene Due, their Head of Communications, explains that their focus is not on revenue but on outreach, attracting new artists and creating great "content." And not just any artist will work. Due explains that they focus on artists who can create a VR or AR experience which will only work in VR or AR; if the artist can do it in any other medium, then probably that is best – though she mentions how great she felt Marina Abramović's recent performance work with them was, so it's important to also say that "there is no set 'right' artist for VR projects."

With time, Due suggests that Acute Art will eventually create a platform for VR they can charge for. She explains, "We're going to see the technology be easier for people to have and therefore distribution might change. So, for example, something akin to Spotify, which was really a game-changer for music where you have free music online and all the access of music that you wanted. And now there are enough people on Spotify so they can actually charge a premium for you to listen. So, I think that's kind of the way that things are going to move forward for the arts as well."

Acute Art doesn't have much competition at the moment, so their opportunity appears significant – if they can get people interested in watching VR films made by contemporary artists, whose work (in relation to the wider ecosystem of people producing VR films) is usually rather inaccessible. One competitor in the space is Khora Contemporary, which was also started by a collector. But Khora is more of an online gallery, with an emphasis on sales and dealing art, less of a runway to develop artists, and less well-known artists and curators affiliated with it.

Due agrees that an appropriate comparison with the company might be something like a fabricator, though she also adds that Acute Art see themselves as a research lab, experimental studio or "technical partner." She explains their process a bit more. "The way it works is that we have an initial conversation with the artist. The artist sort of describes what they want to do and then we find ways of creatively producing the work. And we are creative in the technologies we use, so we work with developers, riggers and 3D animators, who traditionally work to develop games and in the cinema industry. So, we take professionals from those areas and build the teams that will follow the artist projects from beginning to end to support it."

Proponents of AR and VR projects for the art world see major possibilities in the technology. For one, Eliasson has said such projects are still in their "Stone Age" period, and there is a huge leap to be made for the technology's capabilities.3 People also see VR as democratizing art, and Due echoes this. "Yeah, I think it [is]. Whereas I think a painting, you know, can be a little bit elitist – maybe sometimes you have to understand certain things or certain techniques – I think VR is an experience. It's your experience. It's comparable to a physical experience."

One issue with VR is that it is, ironically, perceived by some as democratic, even though the costs of the technology are still quite high. Due counters that the technology will get better and cheaper very quickly. She explains, "For example, HTC is coming out with a new headset in two months that's going to be cordless. Technology moves pretty fast, and it's a matter of, I think, a couple of years maybe – it will be a lot more accessible. It's already a lot more accessible with the Oculus Go. That was an amazing move from Facebook, to have a headset that anyone can buy for two hundred pounds; it's cheaper than a phone." She also says we can get fixated on this idea of a headset – but soon, VR might not be typically experienced via a headset. Very soon, with the way technology is moving, it may just be glasses.

Due sees VR possibly playing an increasingly important part of our daily lives. "Maybe that's the route we're going to take," she says. "You know, maybe there is going to be this world and then sort of a virtual world and we will just hop from one to the other." In the face of criticisms of such a world being antisocial – where everyone is in their headsets – she uses the example of Olafur Eliasson's work. "He has thought of this; how to make his experience an experience that you can share with everyone. So, within his VR, which is called Rainbow, you can be up to thirteen people, so someone in China can be in the same experience as someone in New York." She explains that other artists are starting to think about this idea of shared experiences in general, and that we will see more ideas like this coming out as VR and AR projects.

Art and technology projects can date very quickly. If they are not made with the latest and most impressive technologies, people tend to stick their noses up at them; and sometimes it seems these projects have much shorter shelf lives than more traditional forms of art such as paintings or sculpture. Yet Due says Acute Art constantly updates their works, so that they keep pace with new technology. The company has also been playing with the idea that the work gets updated like software does. In this scenario, she explains, the first work "becomes a version one – a little bit how there is Windows Version 94 – and then Windows 97. It still doesn't mean that it's not interesting to see the previous versions, though."

*

Maybe Acute Art, or someone else making VR works, will make the form more commonplace in the art world and engage more artists to create what will be considered virtual masterpieces. VR has already been shown to have major potential for use in the military, defense, aeronautics and real estate industries, owing to its ability to create an environment where someone can create and interact with a complex prototype. (Think complex modelling, remote operation, hands-on experiences (such as assembly) and interaction, or realistically conceptualizing complex changes to a physical space without doing it.) Why shouldn't it do the same for the art world?

Yet in the art world, there seem to be so many forces that will get in its way. First, even if the larger culture adopts major new technologies, the art world doesn't always adopt or value them particularly highly. Film and video have been around since the turn of the century and the 1960s respectively. And other new media, primarily computer-generated, have been created and employed by artists in the past few decades, but all are basically non-existent when it comes to the most valued works in the art world: paintings and sculpture. In other words, for all the talk about "art for all" and the viability of new mediums, the art market, for value's sake, continually gravitates towards unique paintings and sculptures – and even converts other, supposedly more democratic forms into unique versions. Witness the historical editioning of an unlimited medium – photography – to make it more valuable, just to cite one example.

Secondly, a lot of people (including myself) simply don't like wearing or using VR headsets. You become quite vulnerable in a headset; you are unaware of what's happening around you, and you can't see whether people are nearby or looking at you. It can leave you feeling unsafe; and sometimes you just look plain weird, and become easy fodder for people to poke fun at. At public art fairs, it's been noted that people in their Oculus Rift headsets can end up becoming "an unwitting spectacle for other fairgoers."4

Some organizations have tried to solve this problem by creating fully darkened one-person experiences for VR projects. There have also often been complaints of nausea or sickness from using the technology, because it is almost too good, too real. Maybe this will change when the technology becomes glasses (as Due suggests), but I feel that with the advancement in size will come an advancement in the sensation of reality, so I wonder if the nausea issues will actually cease or get worse.

And then there is the expense of the technology. Maybe it will get cheaper – but maybe it won't, as we have seen with the development of smartphones. Oculus Rift headsets still cost around $400, and I wonder what Oculus's motivation would be in bringing the price down. This does not include the cost of a PC, which you need to be able to create the experience and handle the processing power of the device; and then there is the additional cost of displaying VR, which necessitates laying the appropriate wiring, installing a third-person viewing screen and hiring someone to guide visitors in operating the work. Because these things tend to have technical issues, you typically need to hire a dedicated on-site technician to troubleshoot. (And because all this would just be for one work, there is the related problem that these works can't easily service large crowds.) Finally, to generate graphics or a user experience that come anywhere close to what people are used to from their experiences playing video games takes a lot of time, effort, expertise and money. Video game makers, with their massive followings, might not have much of a problem with this; but it is hard to see art experiences having the same opportunities for investment.

1 All Due quotes, unless otherwise noted, are from conversation and correspondence with the author, October 3, 2018 and March 21, 2019.

2 See Kate Brown, '"This Could Really Be Art for All": Why Daniel Birnbaum Is Leaving His Job as a Museum Director for a Career in VR', Artnet News, July 10, 2018.

3 Ibid.

4 Hettie Judah, 'Is Virtual Reality Art the Real Deal?' Garage, January 24, 2018.

Excerpted from A YEAR IN THE ART WORLD: An Insider's View, by Matthew Israel. © 2020 Matthew Israel. Reprinted by permission of Thames & Hudson Inc, www.thamesandhudsonusa.com