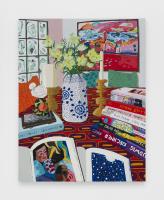

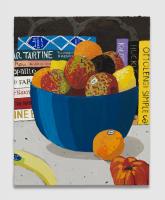

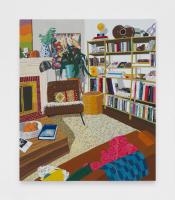

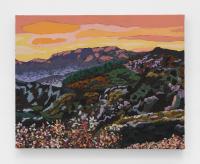

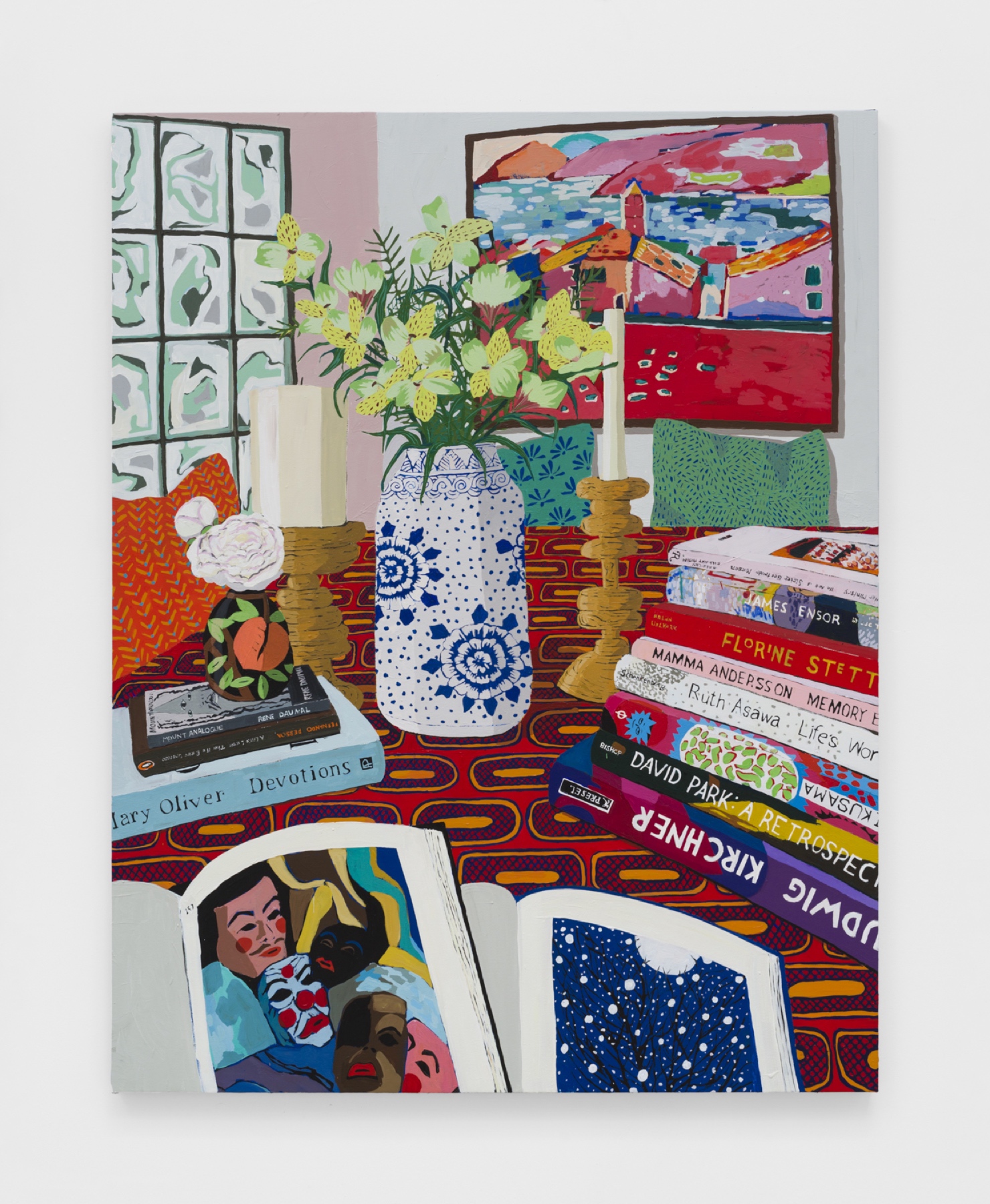

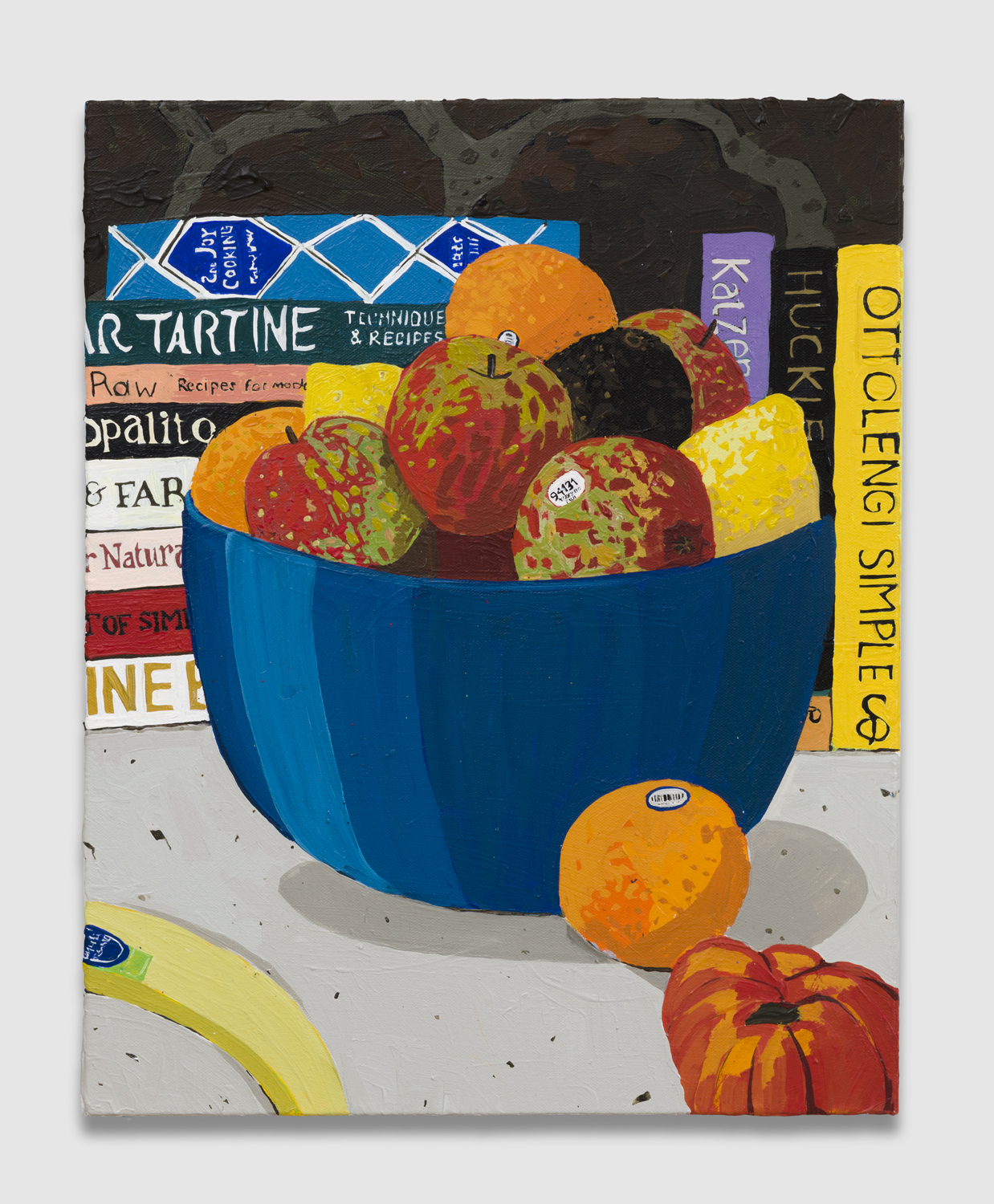

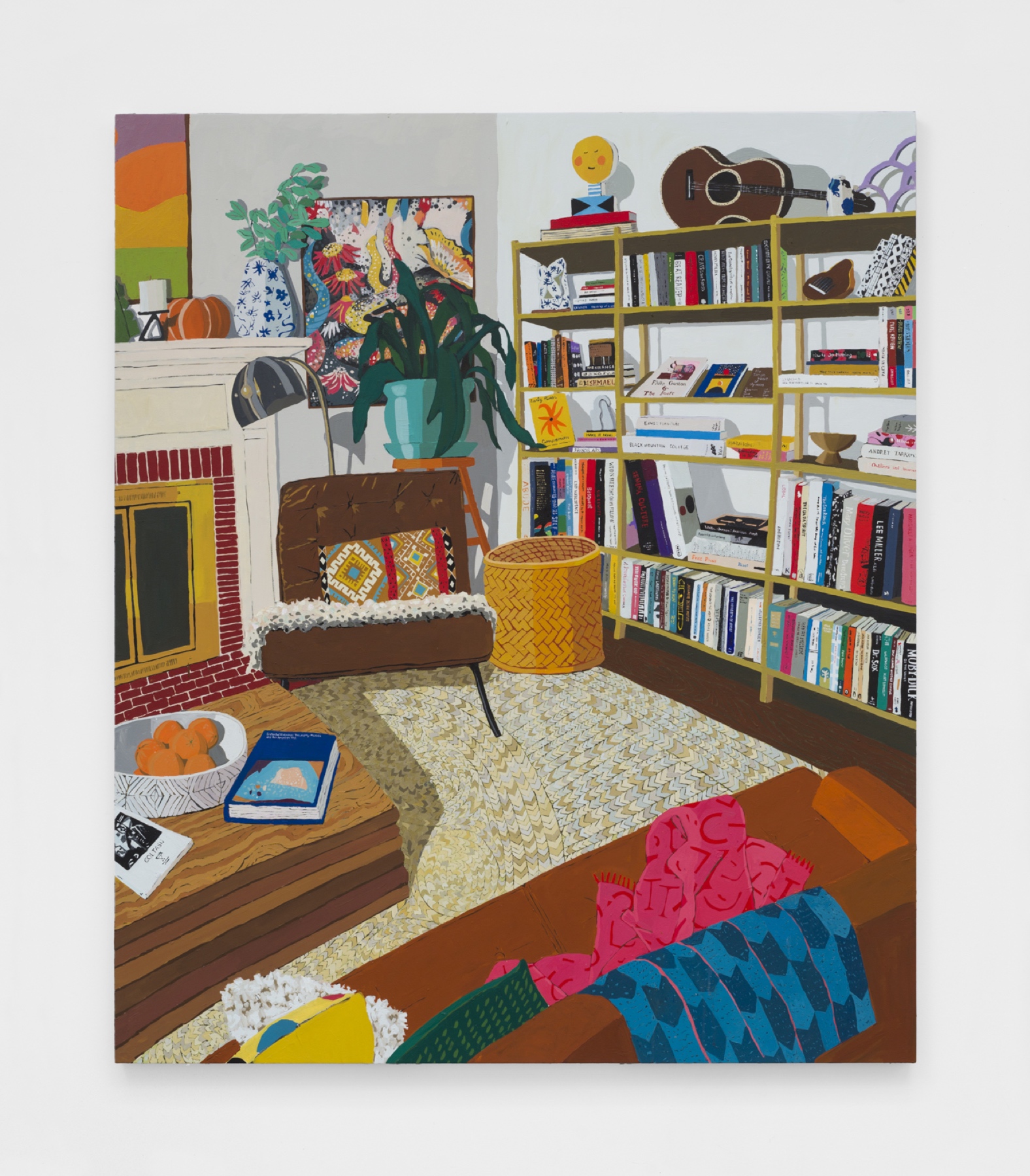

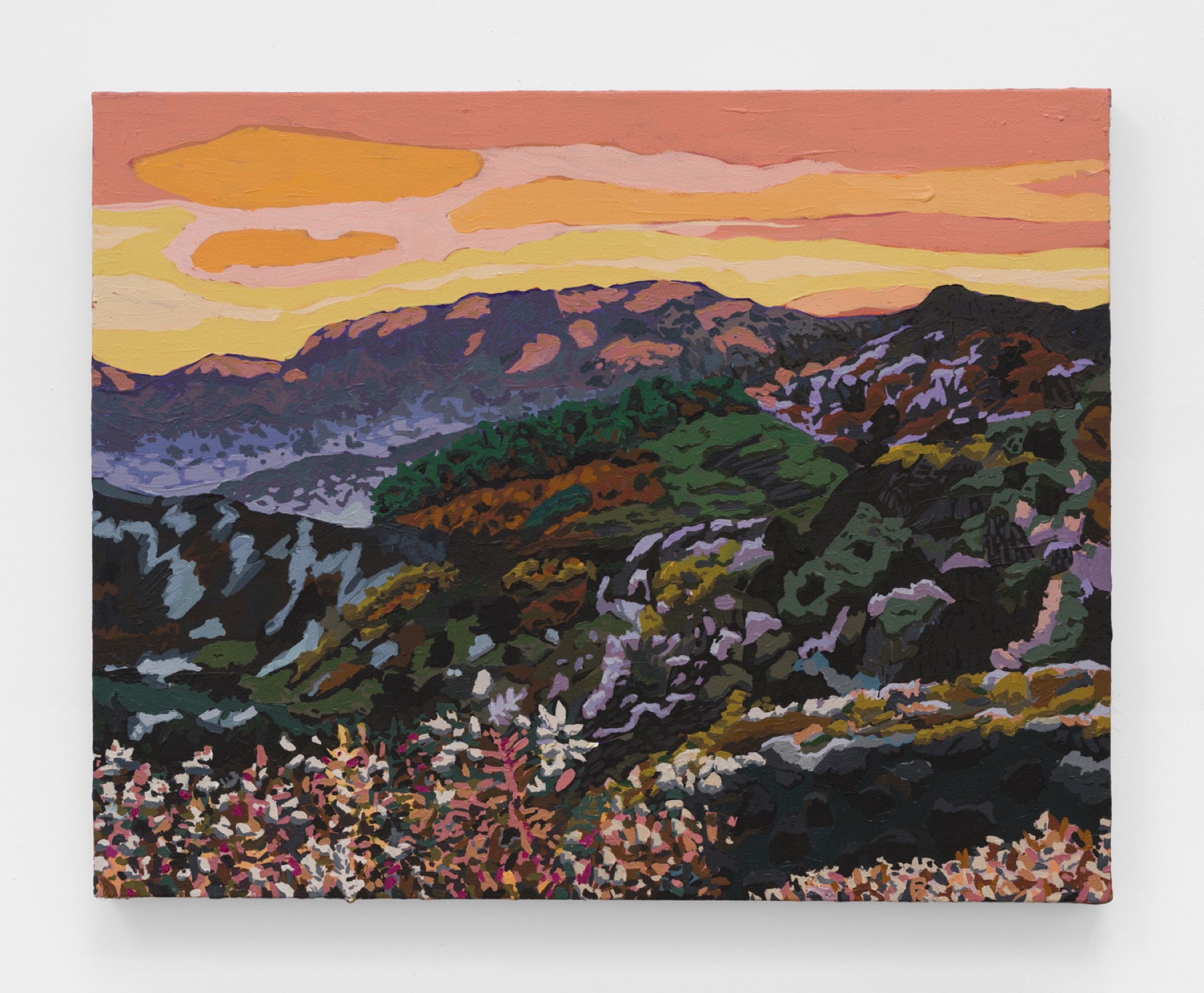

Hilary Pecis specializes in scenes of richly detailed domesticity: the sorts of rooms we all wish we had on our Zoom backgrounds, enlivened by bohemian textiles, flowering plants, and piles of carefully chosen art books. But upon closer examination, her visions of home are nomadic; like many artists the Los Angeles-based Pecis has traveled frequently for work, and so flea markets, storefronts, and Airbnb rentals find their way into her paintings—and give seemingly straightforward environments a bit of intrigue. Her exhibition last summer at Halsey McKay in East Hampton, "Adios Verano," took shape around a road trip to the American Southwest, where she visited Taos and Georgia O'Keeffe's "Ghost Ranch."

In recent weeks, Pecis—like the rest of us—has had to look for inspiration closer to home. Her latest exhibition at Rachel Uffner on New York's Lower East Side, "Come Along With Me," opened in early March just two weeks before regular gallery hours were curtailed by the city's COVID-19 closures. But Pecis is staying positive amid the uncertainty. In an interview with Artful conducted a few weeks into the shutdown, she spoke about being a "tourist" within paintings by other artists, finding silver linings in the shutdown, and where she plans to go as soon as travel picks up again.

Karen Rosenberg: First I just wanted to ask the question I feel like we're all constantly asking each other right now: how are you doing?

Hilary Pecis: I feel pretty lucky that I am still able to work, because there's no one else in my studio. So many of my artist friends aren't able to go to their studios, because they're in shared buildings or the buildings are locked. I have been going there around six in the morning and heading home around noon, because my husband and I have a seven year-old who's having to be home-schooled. My husband is also an artist, so we are splitting up our day evenly so that we each get studio time. I normally would work from about eight to five, so I was able to really focus and get into that flow, whereas right now I'm very distracted. As soon as I start to get going, my brain just shifts gears—I wonder what's going on on Instagram, and the text messages start coming in. I'm trying to pass the time, get quick inspiration, see what my friends are up to.

KR: You're a painter of still lifes and interiors, mostly, and everyone is now trapped in domestic environments. How has that changed the way you approach your subjects?

HP: Still lifes and interiors are deeply rooted in the history of representational painting. There are all these opportunities to noodle away at other artists' or artisans' mark-making, trying to depict something that isn't mine— fonts, or handicrafts, or textiles. It's an opportunity to further my own vocabulary. I get to try out different marks and be a tourist in other people's paintings.

KR: I love that you used the word "tourist." As you said, your work is full of these diverting references to other artists. Who have you been thinking about lately?

HP: One of my favorite contemporary art movements is California Funk, which is having a good moment right now: Maija Peeples-Bright, Joan Brown, Roy De Forest, Robert Arneson. There's something playful and fun about those painters and the work doesn't seem to take itself too seriously, although there's also a seriousness behind it. I typically like work that's accessible, that can be talked about in an academic vernacular or enjoyed by somebody who doesn't know anything about art. That's something that the Funk artists did very well.

I also tend to revert back to the Fauvists: Matisse, Derain. I think there's some comfort there for me—the comfort of looking at an old friend. The first time I'd seen a Matisse was on a poster of The Goldfish, at my cousin's house, and I remember thinking "That is the best painting I've ever seen in my life." It just shifted the way I looked at things. That's what I think happens in these times—we're slowing down, looking at things we've found comforting in the past.

KR: Your show at Rachel Uffner had been open for about two weeks when the COVID-19 shutdown went into effect. What was that like?

HP: People keep asking me, "Are you devastated?" but I'm so grateful it was open for two weeks. I feel really bad for anyone who was planning a show that never opened or got shifted to an online exhibition. This also wasn't my first New York show, and I think that would have been a lot harder. I would love for it to have been open to the public for two months, like it was supposed to be, but two weeks sounds luxurious right now.

KR: How do you think your work is experienced online? What comes across, or doesn't, in that format?

HP: The biggest difference would be the scale. It's really hard to deduce the scale without having a model standing in front of the work. Even in the images with the work installed where you can see the floor, you really don't grasp how big they are. The one I'm working on now is fairly large, 74 inches by 100 inches. Other than that, though, they do translate pretty well online.

This is a great opportunity for collectors and gallerists to see work that they otherwise wouldn't. It's also an equalizer. There are a handful of really, really famous artists, and there are millions of other people making really good work that are completely unknown. Social media has brought some of those artists to the attention of a gallerist that might not have seen them before.

KR: Another response to the crisis has been collaboration: galleries banding together to create cooperative online platforms. This is something you have been doing for a couple of years now, as a founder of the artist collective Binder of Women. How did that come together and what did you learn from it?

HP: The idea was that by working together we would lift each other up, and maybe get exposure to gallerists or collectors from one another. I had seen Artists Space and White Columns put out these editioned portfolios. You might buy it because you like artist A, but you'd be getting also B, C, D, E, and F, so you might be introduced to a new artist. We were trying to come up with a title for the group, and one of the members threw out the Mitt Romney phrase "Binders full of women." It's just such a hilarious statement, so we ran with it.

The first edition of four artists did really well. The group is now sixteen artists, and we put out a new binder just this last winter. It's done very well too—it served its purpose of exposing the artists to a new audience.

KR: What's the first trip you'll take when you can travel again?

This summer I had two trips planned: to Costa Rica and the Hudson Valley. I hope that I can still do both. I was supposed to have work in a group show up at Jack Shainman's gallery in Kinderhook, curated by Helen Molesworth. I've never spent time north of the city, around Hudson, and I have all these plans to visit friends that have moved up there and really check out the area. That was an exciting summer plan, but it's probably not going to happen right away.

In a few months—I say a few months, but it could be six months—our lives will start to roll back into place, and we'll figure out how we move forward. If you saw L.A. right now, though, it's so incredibly beautiful. There isn't the tiniest bit of fog, and there's nobody on the roads. There has to be some kind of silver lining to all of it.

Captions (all paintings courtesy the artist and Rachel Uffner Gallery): Portrait of Hilary Pecis in her studio, courtesy the artist; Hilary Pecis, "Lilies," 2020; Hilary Pecis, "Fruit Bowl," 2020; Hilary Pecis, "Visiting Michelle," 2020; Hilary Pecis, "Santa Monica Mountains," 2020.