In 1975, the artist Gordon Matta-Clark took a chainsaw and a blowtorch to the walls and ceiling of a dilapidated shed on Manhattan's Pier 52. He cut holes in the structure, including a half-moon-shaped opening at the Western end, turning what had been a clandestine center of queer culture into a porous, sunlit cathedral (albeit one that was not recognized by the police department, which nearly charged the artist with vandalism).

The project, which Matta-Clark titled Day's End, was demolished after two years but, like many of the artist's architectural interventions, has lived on through film and photography and in the minds of those who were fortunate enough to witness it. It certainly made a powerful impact on the artist David Hammons, who has devised a tribute to Day's End—a sort of skeleton pier, with thin metal poles anchored in the river that trace the outline of the shed transformed by Matta-Clark. Hammons's design is now being realized by the Whitney Museum, which sits across the West Side Highway from Pier 52 and will debut the new Day's End there in December.

In the meantime, the museum has installed a little teaser of a show in its lobby gallery. In "Around Day's End: Downtown New York, 1970–1986," you can see Super 8 footage of Matta-Clark making his cuts and other documentation of the original Day's End. Here too are works by other artists who frequented the piers, sometimes as observers of the anything-goes scene and sometimes as participants, and a few complementary responses to other blighted areas of the city.

As New York again seems headed into a period of financial and physical precarity, it's worth revisiting the scrappy and audacious art of Matta-Clark and his contemporaries. Just a short while ago, curators were using such works as a counterpoint to rampant overdevelopment and gentrification; in a city somewhat hollowed out by COVID we are less apt to romanticize abandoned and decrepit spaces, or to overlook the mood of desperation and anxiety that underlies some of the art in "Around Day's End."

.jpg)

One highlight of the show is a series of brief but trenchant street performances from 1981 by Hammons, captured in black and white photographs by Dawoud Bey. They show Hammons interacting irreverently with a sculpture by Richard Serra, so as to force a collision between public art and basic human needs; he urinates on its steel surface, which has already been defaced with graffiti, and tosses pairs of shoes over the top of it. In another shot, and one which resonates broadly today, Hammons is seen producing identification for an inquisitive police officer.

The photographer Alvin Baltrop, like Hammons, posed questions about personal autonomy and privacy within public spaces. Baltrop, who was part of the gay underground community of the West Side piers, documented it thoroughly and from multiple perspectives; among the photographs at the Whitney are a close-up portrait of the trans and gay rights activist Marsha P. Johnson and a more distant shot of a collapsed building in which you can barely make out the figures of two men having sex at the water's edge.

The waterfront is a different kind of playground in Joan Jonas's mesmerizing video Songdelay from 1973, in which multiple figures seem to conduct strange rituals or pass coded messages to each other and the viewer: they clap wooden blocks and turn cartwheels in giant hoops, to name a few sequences. As the title suggests, the sound is not synchronized with the action. There is a sense that two parallel experiments are going on: Jonas and her collaborators are exploring the perimeter of Manhattan as they test the limits of what was then the relatively new medium of video.

About a decade later, in 1985, Hammons took part in a more extensive set of performances organized by the nonprofit group Creative Time on the landfill that was to become Battery Park City. For his contribution, which he called Delta Spirit, he built a screened porch and picket fence from found objects like bottle caps, tin cans, and wood scraps. An early sketch for the construction, which served as a set for Sun Ra and other musicians, is at the Whitney and reminds us that Day's End is not Hammons's first public art project along the New York waterfront.

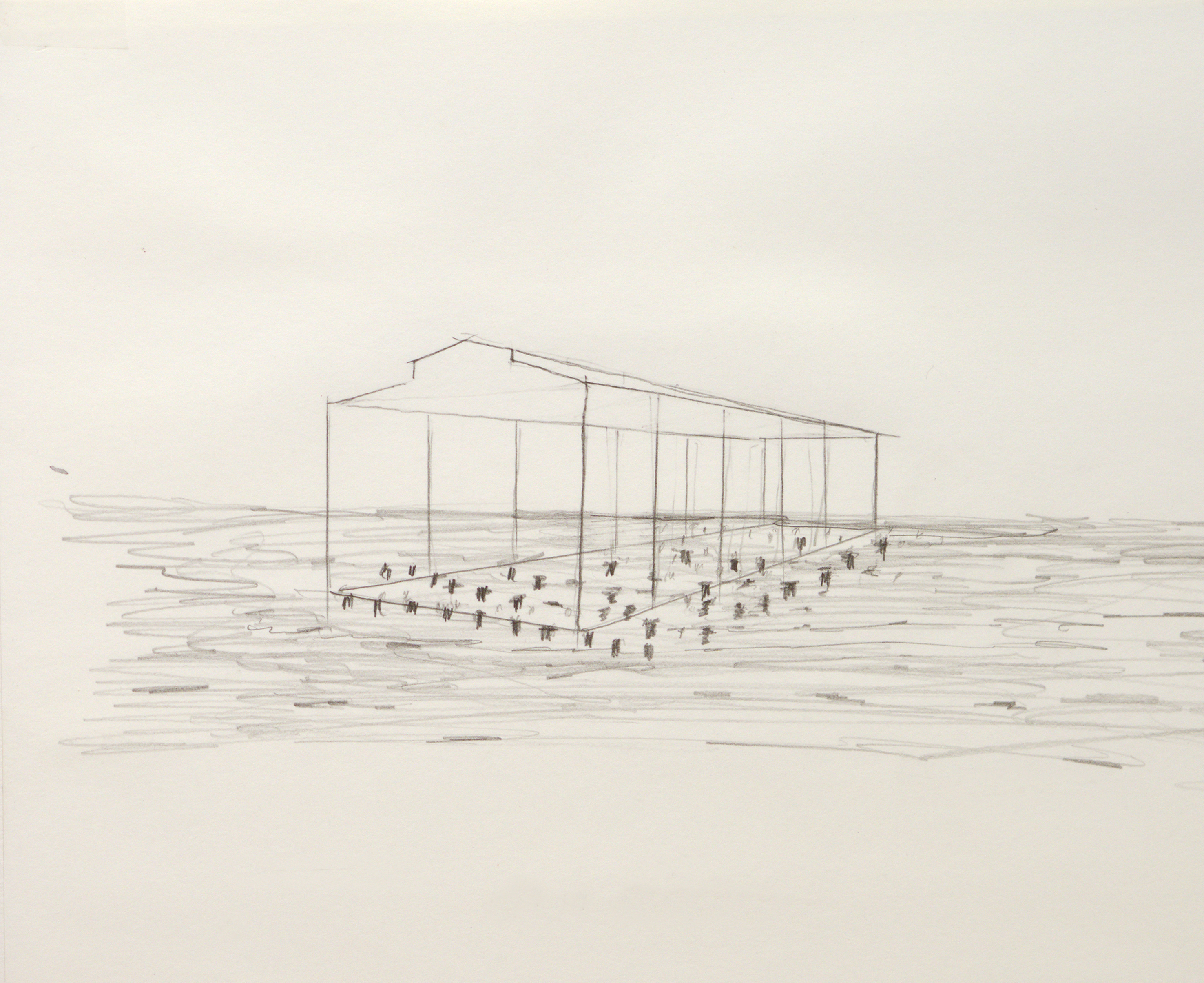

Also in the show is another sketch Hammons made in 2014, when he first conceived his tribute to Matta-Clark. He probably did not imagine, back then, that by the time the Whitney was able to bring his vision to life, the city would be reeling from a pandemic and financial crisis. The museum has called the new Day's End a "ghost monument," but in this haunted year of 2020 it will be many other things: a safe outdoor art experience, and an invitation to artists to make what they can of this moment in the city's life.

Captions:

1) Rendering of the proposed project, Day's End by David Hammons, looking west from Gansevoort Peninsula. Courtesy Guy Nordenson and Associates.

2) Gordon Matta-Clark, (1943-1978). Day's End (Pier 52) (Exterior with Ice), 1975. Color photograph, 1029 x 794 mm. © Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark, Artists Rights Society (ARS), N.Y.

3) David Hammons (b. 1943), Sketch for Day's End, a proposed public art project.