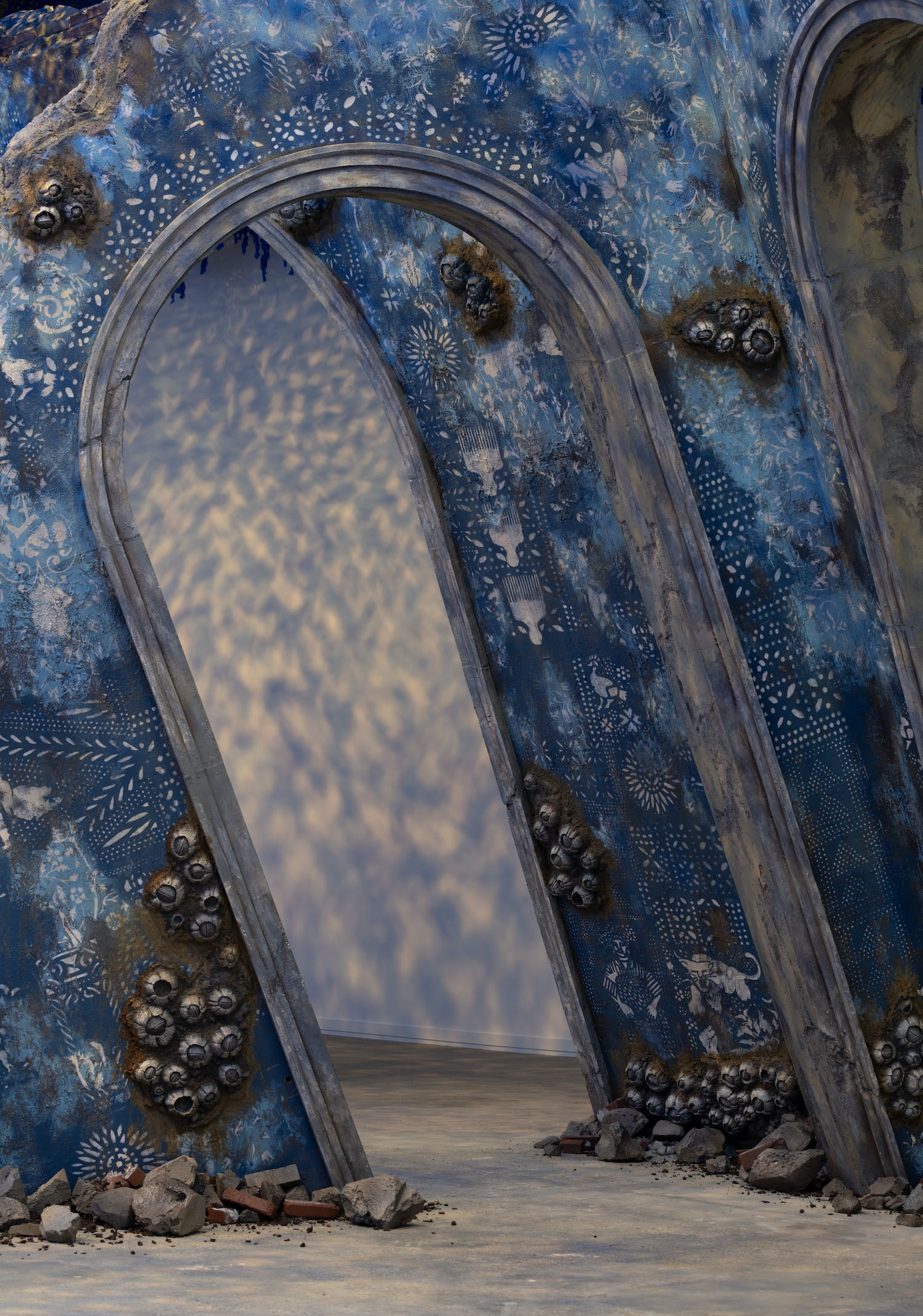

Visitors entering the ICA Boston’s satellite space, the ICA Watershed, this summer will step off the shuttle boat that runs between the two buildings and into what looks like the flooded remnants of a previous civilization. Passing through slanted, arched doorways and beneath a deep indigo blue canopy, they will hear voices murmuring in several languages and puzzle over wall paintings of intricate patterns, maps, and symbols.

The installation is by Firelei Báez, an artist who was born in the Caribbean to Dominican and Haitian parents, and the longitudinal coordinates in her title for the project—To breathe full and free: a declaration, a re-visioning, a correction (19º36’16.9”N 72º13’07.0’’W, 42º21’48.762’’N 71º1’59.628’’W)—offer some clues for the wayward mariner. One specifies the location for the Sans-Souci palace in Haiti, a UNESCO World Heritage site dating from the early 1800s that housed King Henri Christophe following the Haitian Revolution and was subsequently damaged by an earthquake. The other refers to the Watershed site itself, an active marina in East Boston that has played a significant role in trade and immigration.

In connecting these two places—folding the map, so to speak—Báez is encouraging viewers to see American and Caribbean history as deeply intertwined. And although she is inspired by the past, she is also leaving plenty of room for futuristic and fantastical speculation. Sans-Souci is one point of reference for the project, but an equally important one is the mythical “Black Atlantis” known to science fiction fans as Drexciya.

In a conversation with Artful’s Editorial Director Karen Rosenberg, Báez spoke about creating her fictional environment and how it challenges us to see “historic” sites in a new way.

Karen Rosenberg: Your installation links two spaces deeply connected to national identity and heritage in their respective countries, the Boston waterfront and the Sans-Souci palace in Haiti. What led you to bring them together?

Firelei Báez: It’s a project of making things visible, or bringing things to light that have been present but not acknowledged. I’m half Dominican and half Haitian, and part of my work has been to invert the narrative I inherited as a young person—that the Caribbean was ahistoric, that it was there primarily for other people’s pleasure. When people think of the Caribbean they think of a vacation spot, but it’s far more than that.

As I grew up going between the United States and the Caribbean, I came to understand how intrinsically they are linked—how this place I came from was at the forefront of economies and capitalist structures. There’s been a lot of research on how even our nine-to-five workday was developed from enslaved labor systems in both the Caribbean and the U.S., trying to “maximize productivity.” It came out of a certain manipulation of bodies and nature.

This particular space, the Watershed, was a throughway for a lot of raw materials coming in from the Caribbean and it created a lot of American wealth and identity. If you think of the American flag, for instance, it was made of cotton and indigo. At one point, you could trade a human being for a bolt of indigo cotton.

What is your experience of the Sans-Souci palace? Did you visit it growing up?

I knew of it growing up but had never visited in person until after college. You take things for granted—it’s like, I live in New York but I’ve never been to the Statue of Liberty. You think, “It’s going to be here. Of course it’s part of our history, but it’s a tourist trap.”

When I finally went there, I appreciated the immense effort the building of this monument required in a world that, at the time, thought of the Black body as three-fifths of a human. It’s a declaration of humanity, of bodily autonomy. It required an incredible hopefulness, an energetic shift. It’s awe-inspiring, and I wanted to honor that.

Since George Floyd’s murder, there has been so much talk about making things visible. We cannot look away. But that effort to have us all see these things, to collectively get to something different, more inclusive, and better, has been there for so long. It’s a constant push and pull. Appreciating the moments we have achieved, the progress that’s unacknowledged but still there and has contributed to the freedoms we take for granted today, is part of that project. In any work I make, I’m trying to figure out how we got to where we are today, and sharing that with other people to see if they’re willing to take the journey to understand too.

Coming back to that perception of the Caribbean as “ahistoric”: The Boston waterfront has its own history as a revolutionary site. How does that overlap with or complicate your reimagining of Sans-Souci?

They’re not two separate threads. It’s one shirt. That moment of the creation of that architectural space, Sans-Souci, came right around the time of the U.S. acquiring the Louisiana Purchase. We are more than we think we are, both in the Caribbean and in the U.S. As much as there are these power dynamics, there has been constant flow. Chicago was founded by a Haitian-Caribbean. A lot of the things that are foundational to American identity are not acknowledged, but that doesn’t mean they didn’t exist.

In your installation, you are not only re-creating some of the features of Sans-Souci but also making the site look like it’s underwater, as opposed to on a mountaintop where the actual Sans-Souci in Haiti is located. Why did you make that choice?

I thought of it almost like a giant coral reef. Have you ever heard of the Drexciya myth? It’s like a Black Atlantis. According to the myth, which was conceived by two DJs from Detroit in the 1990s, the fetuses of pregnant women who were thrown off of slave ships survive to form a technologically advanced underwater civilization and, ultimately, go into outer space.

For a lot of Black and Brown teens, certain spaces seem inaccessible until you can create these fantasies to help access them. Naming something and creating space, even if it just seems like myth or folklore, is a tool of potentiality.

Are there perhaps themes of climate change here as well, in the idea of a flooded or underwater space? For one thing, the ceiling of the installation echoes the blue tarps that are often used to provide temporary shelter in hurricane-ravaged areas and other disaster zones.

There have always been hurricanes in the Caribbean—Shakespeare speaks of them in his writing. But the acceleration of any climate shift becomes very evident there before it does in other places. There are coastlines that are radically different now than they were even twenty years ago. Growing up there and in Miami, seeing that change accelerate, it was undeniable. I remember, even in middle school in Miami, understanding why certain highways were being moved. We are so primed for thinking of 2050 as a point of acceleration, but we’ve already been experiencing that within the Caribbean and Florida and Texas and New Orleans.

As a child, the tarp was something that was always there. I saw it as something magical and mutable. For adults who had to scramble for safety that probably wasn’t the experience, but the experience of materials is so different when you are a child. The sculpture itself is made out of everyday materials, everything you would use to make a wall in your home. It’s plaster, house paint, sheetrock. These are very familiar things, but it’s in the handling that they become something wondrous and suggest other geographies and things like barnacles and boulders.

Blue is such a loaded color, too. In the Western canon we have different histories and etymologies of blue, for instance the Virgin Mary Judeo-Christian understandings of it. I’m using it to create a space for introspection, as in West African pantheons where it’s almost a karmic reset. There’s a deity or energetic force that comes from the ocean. Even in a disaster, a moment of pain and catastrophe, we can think of the ocean or the night sky as a space of healing.

It also seems significant that visitors to the installation can actually approach it by water, via a shuttle from the ICA’s main building. Even before they arrive, they are physically connected to histories of trade and immigration.

In breathing in that salty air, in feeling the breezes in their faces as they’re taking that boat from one place to the other, visitors come into the sculpture with their senses primed and their guards lowered. I want this to be a space to reconnect with oneself, with the body, with the idea that we are beings in relation to each other. The incredible theorist and writer from the Caribbean, Édouard Glissant, informed a lot of contemporary art practices with this idea that the water, which can be seen as a separator of spaces, can also be a connector.

That’s also reinforced in the sound that runs through the installation. The audio comes from an open call in which you asked people to talk about their experiences of migration and the idea of home.

People’s definitions of home and their experiences of migration became especially poignant during the pandemic, when some of us were stuck for long periods away from home, or became homeless, or were only at home. And the Watershed itself, historically, was a vetting point for many migrants from all parts of the world coming in through Boston. People were coming in through Ellis Island or East Boston.

I also was thinking about the tradition of calling back to ancestors for guidance. In Asian traditions you have that, in West African traditions in Latin America you have days that you honor the dead or spaces you dedicate to them in your home. Maybe the sound you hear in each of the doorways in the installation is a way of calling back to the ancestors.

I wanted the sound to be almost like a wash. Even though consciously you might not hear one story or the other in full, the overlapping of two or three or seven stories in your mind will create something entirely new. I’m interested in how viewers can create something new with what they hear.

You mentioned the pandemic. You have created such a wonderfully immersive installation, a sort of antidote to the experience of being stuck at home for so long and not being able to interact with art physically or go into these kinds of spaces. Was this on your mind?

Absolutely. We have been so separated, and as much as technology has been a gift that we can do all these Zooms, we haven’t had all those nonverbal cues—we haven’t been able to hug or see art, let alone touch it. I want people to go in and climb the walls, to be physically present, joyful, and together.