From the beginning of her career, some twenty years ago, the painter Julie Mehretu has been drawn to sweeping themes of urbanism, geopolitics, conflict, and migration. No subject, it seems, is too big for her large scale and intensively researched canvases, which have combined details from architectural renderings with more expressive abstract marks.

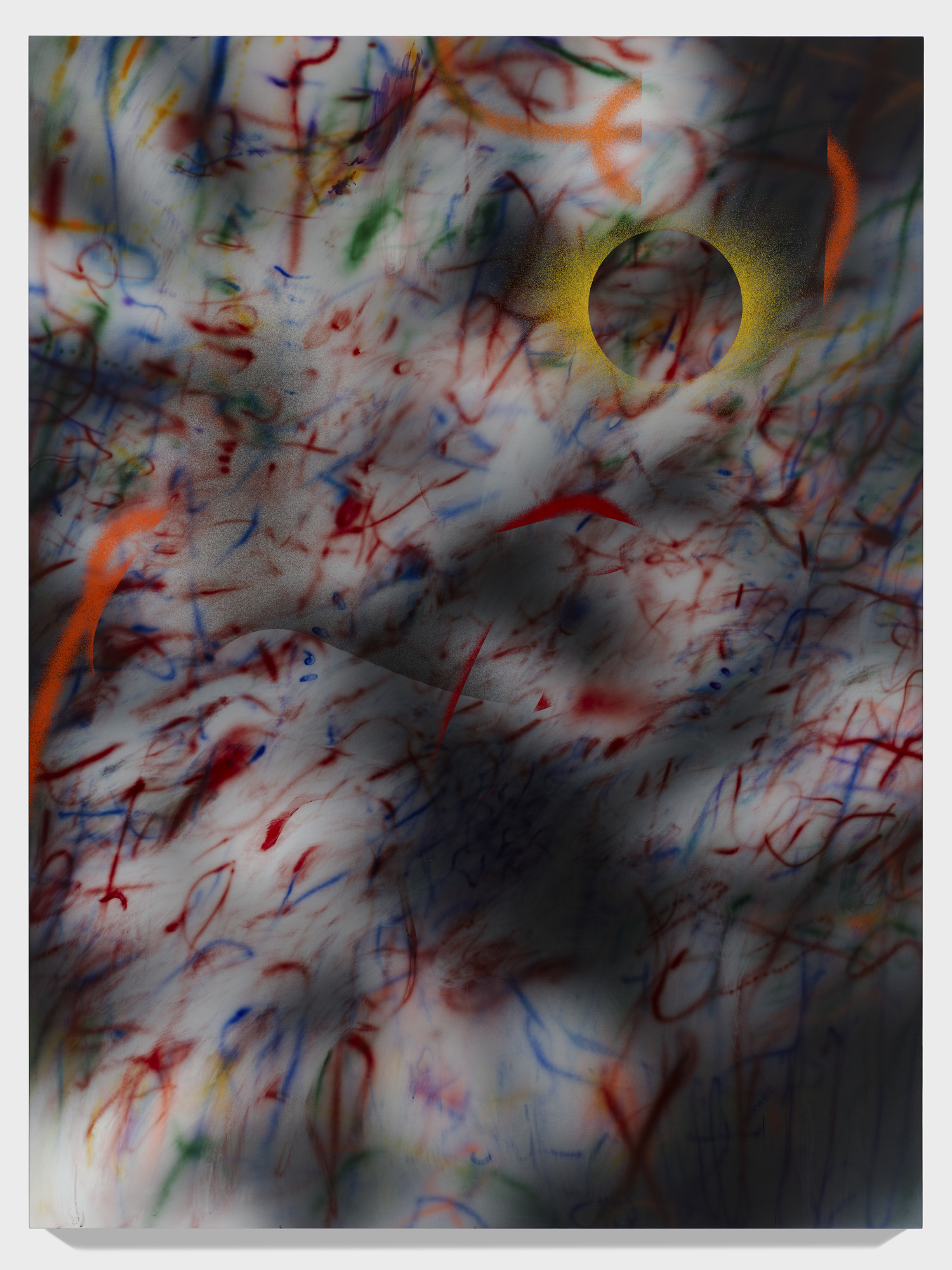

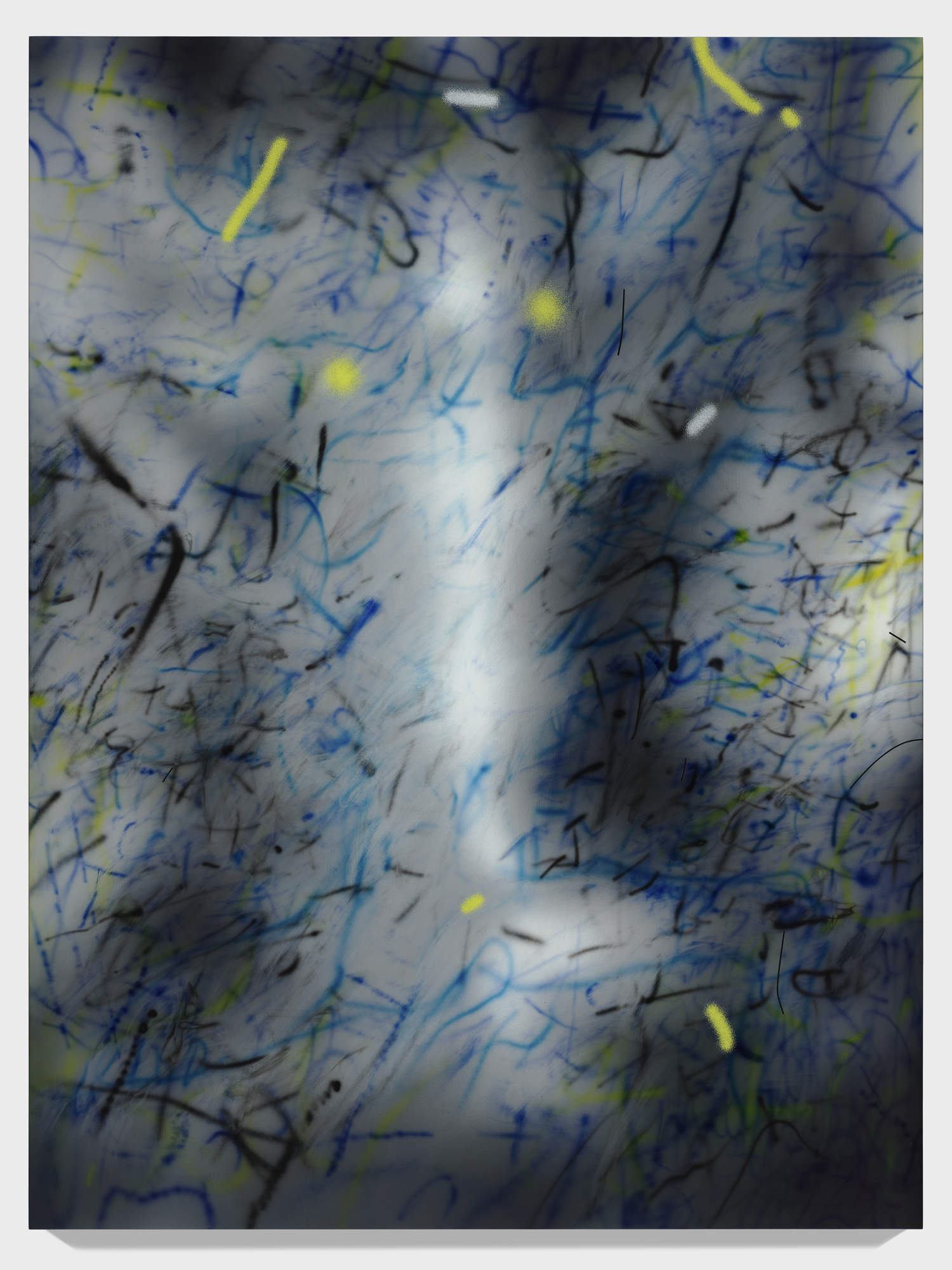

Now, Mehretu has added to that intimidating list of topics our new global pandemic. Making art in and about Covid, however, required some adjustments to her process and her painterly language. After leaving her New York City studio during the shutdown to work in the Catskills at Denniston Hill, an artist residency she co-founded, Mehretu found herself embracing the isolation and introspection—and, above all, the state of uncertainty. In a reflection of the unresolved feeling of the time, she started to play with blurred photographic imagery and used an airbrush to create fuzzed wisps of lines.

The paintings she made upstate are now at Marian Goodman gallery in New York (through December 23), along with other works that commenced a year or two earlier but were completed in the miasma of 2020. On the occasion of the New York show and her first traveling museum survey, co-organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art and currently at the High Museum in Atlanta (through January 31), Mehretu spoke to Artful's Editorial Director about the new direction in her work.

Karen Rosenberg: I want to start by talking about the paintings you made while living upstate during the early months of the pandemic. They seem to represent a new direction in your work, and take up a separate gallery of your show at Marian Goodman. What was that time like for you?

Julie Mehretu: Before the pandemic we were here in New York City, the kids were going to school, and I was working at my studio. I had just been in Dhaka, for the Dhaka Art Summit, and I remember being nervous about going there. All the news seemed to point to our ending up in this situation. Soon enough it came, and we decided to go upstate, because we had this space, Denniston Hill, that is usually an artist residency. We just packed up a U-Haul truck with these seven panels that I had prepared. I thought maybe I'll just be up there during spring break and at least I'll get something started, and it soon became very clear that this wasn't going to end anytime soon. The kids were not going to go back to school.

The whole world had changed in that week. All the failures of our time were exposed, and we really felt the collapse of any idea of progress. I worked on those paintings from that space. I was listening to Moby Dick at night—I have insomnia, and I listen through the night—and I can't imagine a better book to have as a companion through those first weeks of the pandemic. My thinking was really formed by that time and its sense of suspension. How do you build and imagine something in these moments of precarity? What can come together? I don't think that these paintings are trying to answer that in any way, but these were the ideas I was thinking through.

There's a very different intentionality in these paintings. They came very quickly. I had hours to work every day. I was home-schooling at the same time, but I had a lot of time to read, listen to music, walk through the woods, and work. It was a kind of suspended and internal and inquisitive time, and I feel like that's very apparent in the paintings.

KR: How did it feel to suddenly become an artist-in-residence again, so to speak, at Denniston Hill? This was the Catskills retreat you founded with Paul Pfeiffer and Lawrence Chua back in 2004, and where you made some important works of your early career.

JM: Denniston Hill was always an artist residency, but it's also a laboratory. We try to think about ecology, the stewardship of the land. We always had farmers-in-residence as well as artists-in-residence. It was about bringing these different forms of creative thinking and making together, whether it's like my work, a very formal practice in the studio, or Paul, who does a very different kind of video-based work, or Lawrence, who is an architectural historian. Since the pandemic we have really tried to rethink the program, building around the idea of Exodus. Our interest is in those years of loss in the desert from that story. Not the promised land, but the post-emancipatory time of confusion—the haze, the blur, the uncertainty and unknowing.

There's an interesting book by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World. She's an anthropologist studying the ecology and economy of the Matsutake mushroom. It grows in forests and lands that have been destroyed by humans. In the American West, there are deforested regions where this mushroom is thriving and where refugee foragers from Laos and Cambodia know how to look for it, and there's an entire economy around that. But it's all an economy of precarity. It's about how we invent something within the state of destruction we're in, how we continue.

KR: There are striking differences between these hazy, blurry pandemic paintings and the earlier, denser works in the exhibition that represent some longstanding themes of your art, such as mass gatherings and uprisings. How has your relationship with this subject matter evolved?

JM: I have been so immersed in these ideas around collective gathering and the individual within the collective, how you have this history of protest and agency within the collective. Early on I was trying to understand the utopian desires that made me, that are really primal and core to what I am. The late 1960s and '70s was this time of world-building, decolonization, my parents trying to work toward a different Ethiopia, and this happening all over the continent of Africa. In this country you had the Civil Rights Art in '68 and you had a different kind of imagination of what was possible in the '70s, which got dismantled in the '80s. For me, it was always, how does the individual find agency within all of that? The marks and the architecture are in this dynamic, but how can the marks fundamentally change that?

KR: Looking back over the last few years of your paintings, there is also a definite shift away from architecture—from the maps and blueprints that have long served as a stage for your more gestural mark-making.

JM: What was important to me in the paintings at a certain point was the visceral, time-based experience in front of the painting. And the more I started to look at that, I saw the architecture as a limit. About five years ago I started to work with just gray surfaces, and invent something from the marks themselves.

KR: The marks have changed too. In this new show you're using the airbrush a lot, sometimes exclusively.

JM: The paintings that I worked on during the pandemic, there's no brush mark in them. They're all done with airbrush. There is the hand, because the hand works with the airbrush, and there is the erasure in the background made by sanding and using a towel. Sometimes there are finger marks. But there aren't really brush marks.

It's something that I had been pushing even before the pandemic. The removal of the hand or brush had become a challenge—what would emerge when you remove it? I had made a painting after the Grenfell Tower burning, a black and white blur, and it felt like this specter of everything that took place in that fire. I had thought the airbrush would just be a base layer to get me into the painting, and instead it became one of the most haunting paintings that I had made.

Also, during a different moment I wanted to work differently—and as radically as I could in what is a very slow, mediated process. Painting is very slow. And changing it is slow.

KR: Behind the layer of airbrush, as you say, there is also a blurred underpainting that seems to represent another shift in your technique.

JM: The blur became interesting to me because I projected an image once, a ruined landscape of Syria, and I was going to draw it but the projector was out of focus and that blurred image was so much more potent. As a blur it carried the history of that place, but also the possible future of something that could emerge from that ruin. Potentiality felt present in that blur. It reminded me of these old photographs of the occult where people in early photography tried to actually catch spirits--it was actually these optical things that were happening with photos. It also goes back to the blur of the desert, of unknowing and uncertainty.

Part of my intention with the blur is to move away from the mediated images of social media. If you think of that Marshall McLuhan quote "the medium is the message," that was really different when you had centralized media. How do you build a reality when everybody is in their own different reality? How do you rethink those kinds of mediated images? By blurring it, and using the light and the color and the atmosphere.

KR: What were your source images for these blurs?

JM: All those images come from the past year. The sources are scenes from borders, where you have border patrol in conflict with immigrant communities that are trying to cross, whether it was in Guatemala or on the American border. There are some images of detention centers, also one of the migrant detention centers that was bombed in Libya. It's the two forms of bodies interacting—the representative of the state and the desire of the individual.

What interestes me about that blur is the specter and the haunting, how these colossal figures or disembodied parts of figures emerge in the paintings. There were moments where something came to the fore, and I would usually sand it back if it became too apparent.

KR: Speaking of haunting, a couple of the paintings at Marian Goodman seem to reflect that this has been a time of overwhelming grief. I'm thinking of the painting dedicated to the curator Okwui Enwezor, who died in 2019 and had been writing an essay for the catalogue of your traveling survey, and perhaps also the one titled after Toni Morrison and her 2008 novel A Mercy.

JM: The pandemic has been a time of intense grief. All of us know somebody who has passed away, or know of people who lost people who were very close to them. We were told that this would happen, but it happened rapidly.

I was working on a painting based on an image from the violence in Charlottesville when I got the news that Okwui had died. He and I had been talking about the colonial sublime, terror and violence in the land and landscape painting, and we had been having conversations around these images. The day that I got the news he died I was working on that painting, and I knew right then that it was Okwui's painting. I continued to work on it for a while after that. It's also a nod to the artist Jack Whitten, who made those black monolith paintings for heroes of his who had died. So it's a nod to Jack and Okwui, who were both lost recently.

The Toni Morrison painting comes from a Charlottesville image as well. I was trying to find ways to mine that image, and it took me two years. I created a Rorschach out of it and inverted the colors. I had had it for so long in the studio, this Rorschached reversed image, and then I went back to it after the pandemic started and this painting came out in three days. As I was working on it, Hilton Als called me—he is doing a show based on Toni Morrison books, and he asked me to make a piece. Right away I knew, "I have that painting."

KR: I'd like to end by asking you about the big survey of your work, which is currently at the High Museum in Atlanta in the middle of a national tour. These shows are always an occasion to look back and reflect, and I'm wondering how that process has affected you and your painting going forward.

JM: I don't think I'd be making the work I'm making now if it wasn't for that process. I was fortunate that it took a long time—I started working on it five, six years ago. It made me push harder on where I wanted the paintings to go, what I could let go of, what new things I could explore. Color, marks, gesture, scale, playing with and manipulating photography—all of that became new terrain to explore.