In his monthly column “Impressions,” Artful’s co-founder and chief curator Matthew Israel shares the art world topics he is thinking about—and believes you should be thinking about as well.

In the United States at least there is now a sense that the institutional and logistical struggles the art world has weathered for the past year are beginning to recede. So for this installment of “Impressions,” I am going to focus less on broader observations about the art world as a whole and where it might be heading, and more on the people at the center of the art world: artists. This month I focus on four artists whose work I have been following—some only recently, and others for years.

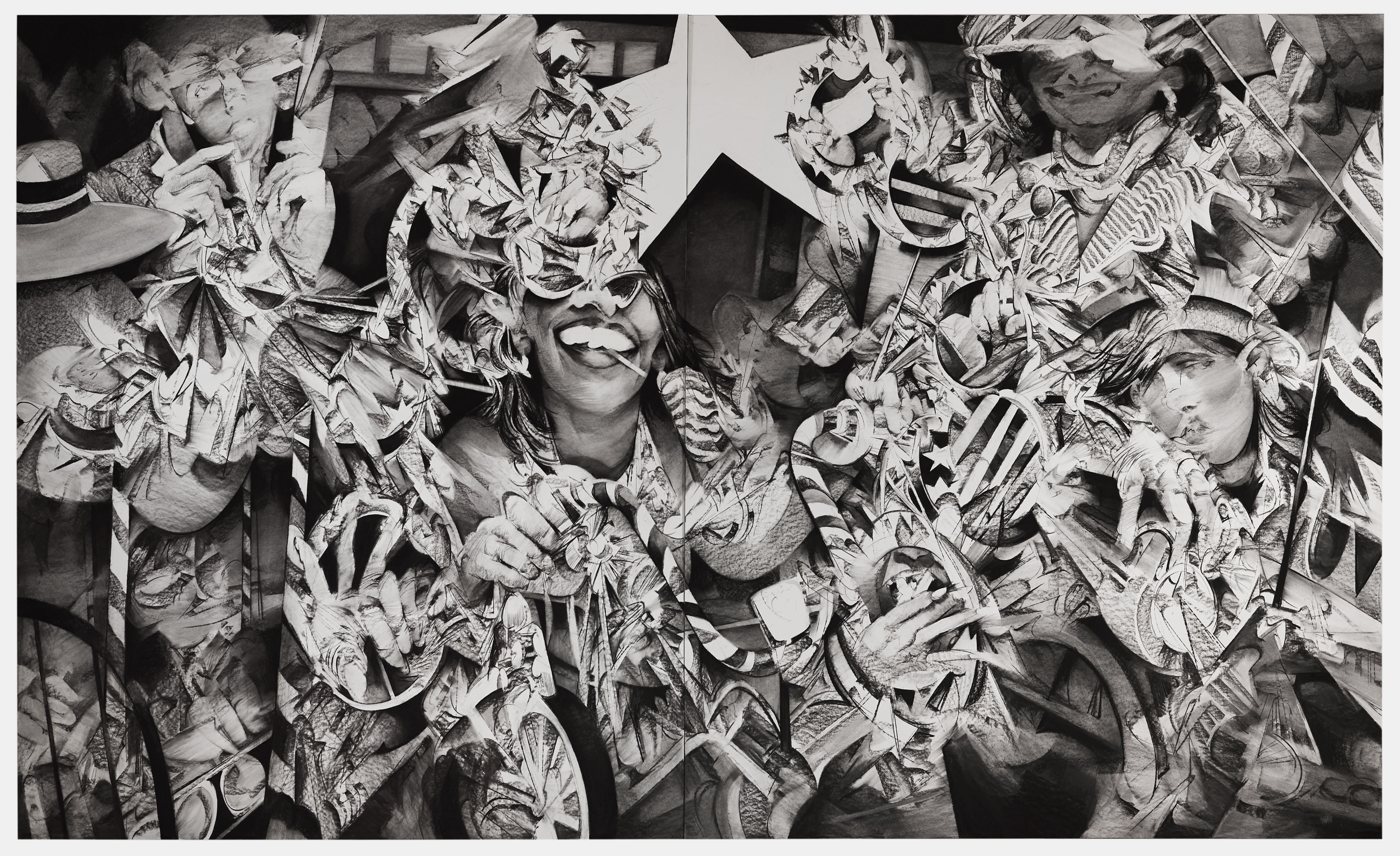

Anna Park

Anna Park’s work really surprised me when I saw it recently on my Instagram feed, because it looked completely out of place (in comparison with other visual approaches currently being pursued). Its allover monochromatic compositions recalled many artworks of previous decades, particularly the black paintings of Willem de Kooning; the large-scale canvases of Cecily Brown or Robert Longo may also come to mind. I keep coming back to images of Park’s work to get lost in them, to try to discern the pictorial logic or find the humans I know exist in them somewhere. And Park’s images can be seen a lot recently. She was included in a large show at the Drawing Center in New York, she has been posted about by the artist KAWS, and she was commissioned to design artwork for Mank, the recent David Fincher film.

Park’s Instagram neatly captures the progression of her work. As you scroll back in time, the work becomes increasingly representational. We see scenes of dinner parties and clearly identifiable figures of women in bathing suits. But as you move back up, toward the present, the works are increasingly more jumbled and abstracted. Aggregations of limbs, objects, and gestures, with a face or body here or there, recall the trail-like mapping of movement the Futurists employed in their works. In the 1950s, this progression towards gestural abstraction was a hallmark of so many artists. I am curious: what does it mean to Park to move in this direction today?

Yuji Agematsu

For the past few years I’ve been kind of obsessed with one of Yuji Agematsu’s series, which could at first be mistaken for trash but upon closer inspection is deeply intriguing. I first came upon his work when I was at Artsy, when Agematsu was part of the first Artsy Vanguard. Agematsu, who is 64 years old, is best known for what he calls his “zips” (not to be confused with those of Barnett Newman). These are collections of detritus he finds on the street walking in New York and then composes in cellophane sleeves of the kind used to seal cigarette packs. Each sleeve represents one day and since 1996, Agematsu has created one every day (recalling the practices of other artists who make such repetitive and scheduled work, principally On Kawara). In 2019, all 365 of Agematsu’s zips from 2017 were shown at the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh.

I find it fascinating how much compositional diversity and play can occur with such humble materials in such small spaces. In Agematsu’s work, a brown hair clip becomes a monolith reminiscent of a large-scale Mark di Suvero sculpture. A blue zipper storage baggie that probably once carried drugs is a stark background to a rock, reminiscent (for me) of the minimal sculptures of Jose Dávila. And a zigzaggy thread of corrugated paper packing material perfectly frames what looks like a yellowish tortilla chip.

Andra Ursuta

Ramiken’s Andra Ursuta exhibition was one of the “it” shows in New York City in 2019. In the exhibition, installed in a vast warehouse space while the gallery was under construction, Ursuta transferred the violent themes and iconography of her earlier work into some of the most seductive and luminous figurative sculpture of the past decade. All of her pieces were cast-glass sculptures that combined her own body and objects—a blend of the animate and the inanimate. Among the more memorable works was Predators'r us, a milky orange-yellow figure in the process of getting up or being knocked down. The figure is headless, with a bottle serving as a stubby arm and large crab-like animals as its feet.

Ursuta creates her works through a laborious process that combines 21st-century and traditional sculpting techniques. She begins by 3D-scanning her body and whatever objects she is working with. She then combines them digitally into her preferred forms; prints them into 3D models; casts the 3D models into wax and wax models lead eventually to cast colored glass. The final works are breathtaking; they at once recall Alien, or the more Surrealist forms of Constantin Brancusi and Alberto Giacometti—but in the end, their forms feel altogether their own, which is highly difficult to do in our contemporary aesthetic landscape. In the past year, Ursuta has joined David Zwirner, and one wonders what she will do with the support, resources, and global reach the mega-gallery will provide.

James Barnor

I’d love to know even a fraction of the stories behind the images of British-Ghanaian photographer James Barnor (who is currently having a retrospective exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in London). Barnor’s work is so varied—it consists of studio portraiture, photojournalism, fashion, editorial commissions and social commentary; it spans Ghana and the United Kingdom; and it's a fascinating history of black life in both places, covering some sixty years of social and political changes in an archive of about 32,000 images.

In the 1950s, Barnor became Ghana’s first full-time newspaper photographer; he is credited with introducing color photography to the country in the 1970s. Throughout his career he went back and forth to London, eventually settling there in 1994. Many of Barnor’s color images of the early 1970s are indelible, and propose a much more expansive and international approach to the history of color photography that has been codified by The Museum of Modern Art and has been told primarily through white men such as William Eggleston and Stephen Shore.

As always, I’m happy to answer any questions about this column via Instagram. DM me @matthewisrael.