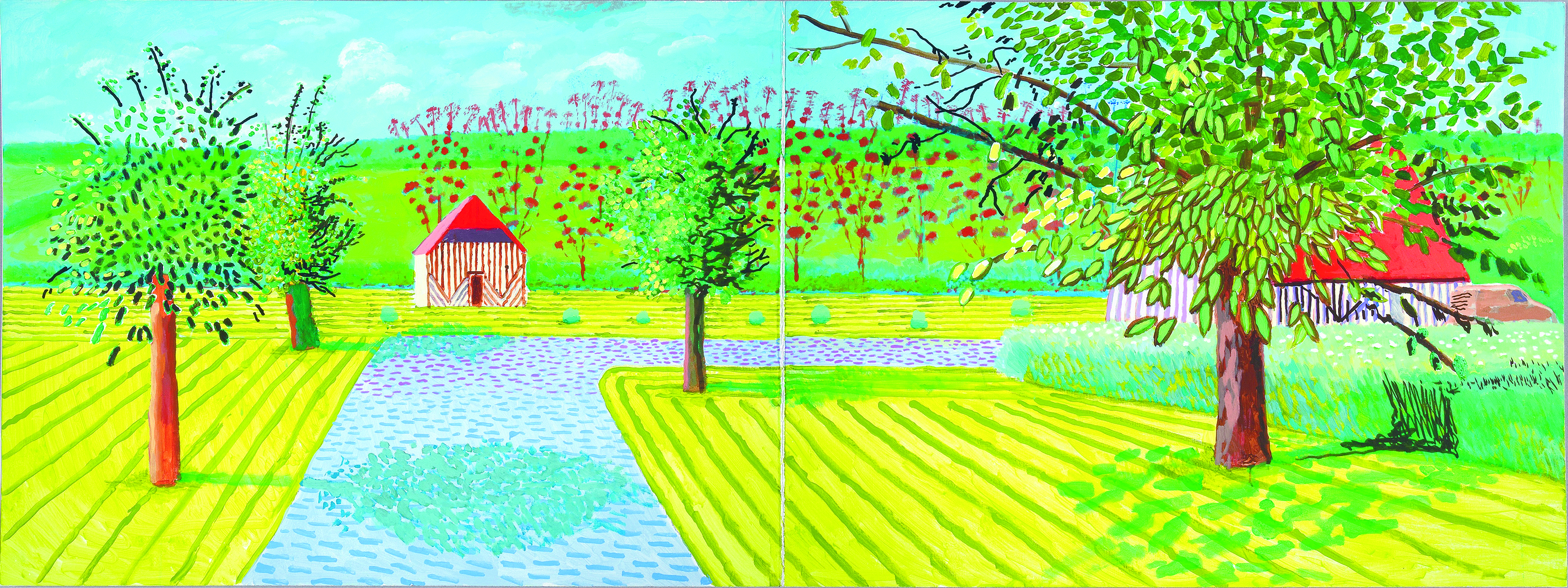

It’s unusual for new work by an artist to make the front pages of a newspaper, but that is exactly what happened in Britain when David Hockney shared images of his latest landscapes with the BBC last April. Hockney, who is in his early eighties, was spending the pandemic happily and productively ensconced in a farmhouse in Normandy; he had arrived there intending to paint the unfolding spring, but extended his stay when the virus hit. Brits suffering through the first of several lockdowns were cheered by the sight of Hockney’s ebullient drawings and his irrepressible enthusiasm for life.

Spring Cannot Be Cancelled, a forthcoming book by the Cambridge-based critic and Hockney correspondent Martin Gayford (Thames & Hudson, May 11), offers a deeper look at the artist’s new Norman phase and his capacity to inspire others. Gayford, who has collaborated with Hockney on two previous publications and is among those the artist entrusts with frequent e-mail updates on his work, writes this insightful book in the form of a dialogue—one that begins in person but quickly transitions, once the pandemic isolates them both, to FaceTime. Along with a close look at Hockney’s process, he captures the artist’s entertaining digressions and discursions on everything from hydrodynamics to an obscure early-20th-century treatise on perspective.

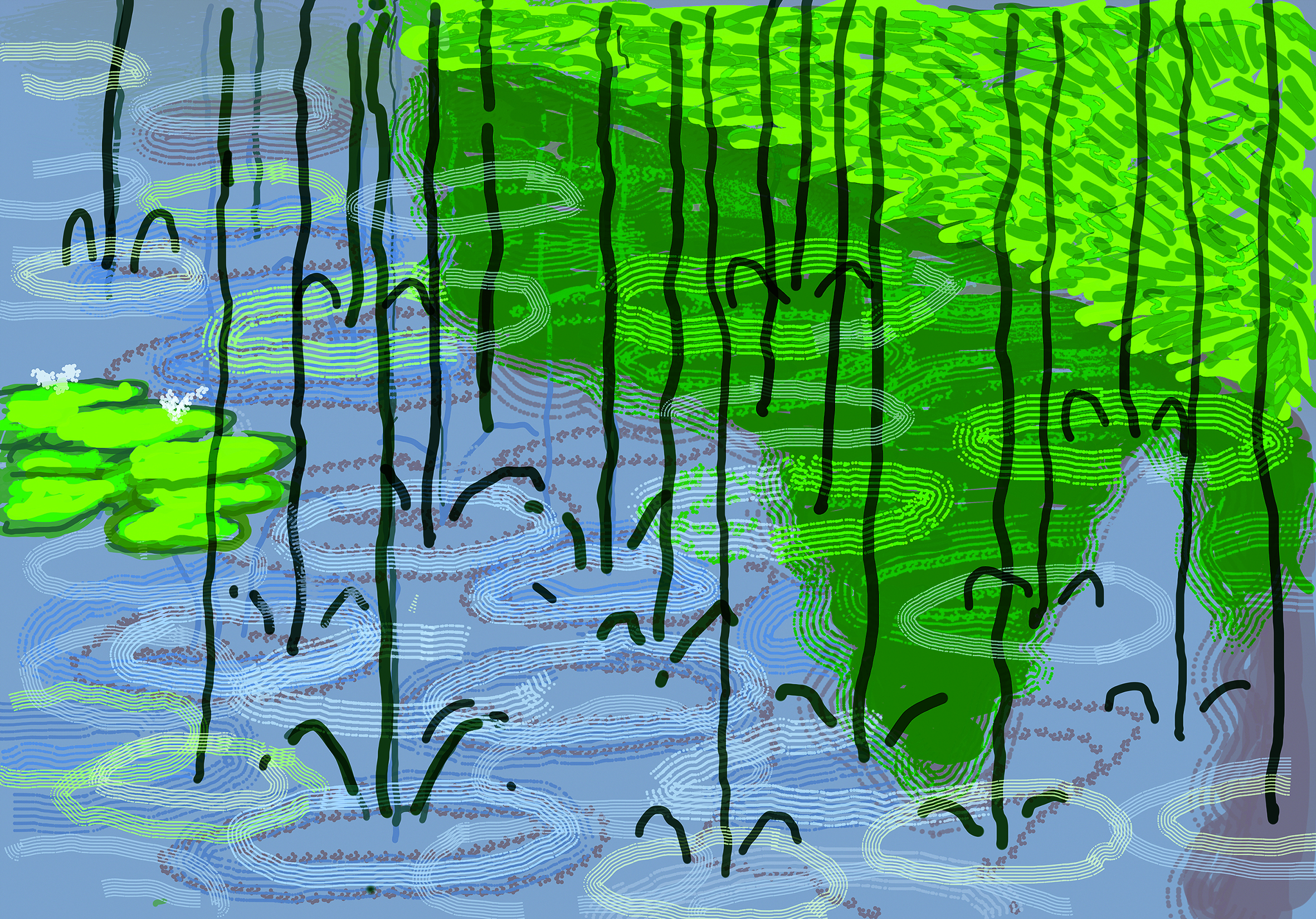

Along with lots of friendly banter between two people who really love art, Spring Cannot Be Cancelled offers numerous illustrations of Hockney’s works from Normandy (many of them shimmering, multi-textured landscapes made, improbably, on an iPad) and of the art-historical masterpieces that pepper their conversation.

Gayford took a break from his latest projects, a compendium of Lucian Freud’s early letters and a history of painting in Venice, to speak with Artful’s Editorial Director Karen Rosenberg about keeping up with the prolific Hockney and learning from his extraordinarily rich life in lockdown.

Karen Rosenberg: Your last book, The Pursuit of Art, was about traveling in search of aesthetic experiences. This one, in a sense, is about not traveling.

Martin Gayford: That’s right. The world changed shortly after I published The Pursuit of Art. It describes all sorts of foreign adventures that are now completely impossible to undertake. The trigger for this new book was that David seemed to have entered a completely new phase of life in Normandy. My initial idea was that I’d visit him from time to time and we’d talk, and it would provide material for a book similar to the one we published about ten years ago, A Bigger Message: Conversations with David Hockney, which is about his life in Yorkshire. But I only managed one visit before Covid turned up and the world shut down. So it changed into something else, which was more, as you say, a book about not traveling and this new world in which we’re all looking at pictures of each other on Zoom and Facetime.

David suggested phoning up at the cocktail hour in France, which is five o’clock English time, so it was the end of the day and we were unwinding. He had already finished drawing and I had finished writing, and we were just chatting. The thing with FaceTime between England and rural Normandy is that sometimes you get a very good signal and sometimes you don’t. There were times when David was saying something interesting and then his face froze and I lost the rest of it.

Besides chronicling this extraordinary year, the book seems to be making a more timeless argument for doing the kind of looking that Hockney is doing—settling into and inhabiting a landscape and really getting to know it on a very intimate level.

That’s right, traveling, as you might say, in depth. Other artists I have known tended to do this anyway, to really dig into a certain spot. The London painters Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach, for example, were great non-travelers. Auerbach likes to say that there’s enough art in London to satisfy anyone who’s not inordinately greedy for masterpieces.

As I say in the book, a lot of great art we admire and go to museums to visit is actually a depiction of the artist’s rather humble surroundings. Most of Vermeer’s work seems to be interiors of his own house, an ordinary Dutch house. His landscapes were within a few minutes’ walk of where he lived, around Delft. It’s the same with Van Gogh, these rather ordinary places he could walk to from his house in Arles. As far as artists are concerned, you don’t have to make a long journey to see something special. Just about anything can be the trigger for a work of art.

Speaking of Van Gogh, in the book you make a historical comparison between Hockney in Normandy and Van Gogh in Arles.

MG: Van Gogh is certainly one of his great heroes, and he was very much on David’s mind just as he arrived in Normandy because he had recently been in Amsterdam opening an exhibition at the Van Gogh museum, in which his work was placed side-by-side with Van Gogh’s. His drawings from around that time are quite visibly affected by Van Gogh—you can see Van Gogh’s lines.

He also said, when he was in Yorkshire, that he thought Van Gogh had got so far so fast partly because he was on his own. Not that David is quite on his own, but he had moved to a pretty quiet corner of Yorkshire and was just seeing a few people, his assistants and others he was working with. He felt that those circumstances aided concentration, so he could get into this state he talked about last year where he worked during the day and went to bed thinking about what he had done that day and woke up knowing what he was going to do the next day. It was just a continuous process.

In your dialogue he also likes to quote a maxim Rembrandt passed along to his students: “Do not travel, not even to Italy.”

Yes. For some time he’s been saying that he’s had enough of intercontinental travel and jet lag. For years he was flying between Europe and Los Angeles quite frequently. You come to a point where you’d rather do as little as possible of that sort of thing. David had always planned to just stay in Normandy and depict what was around him, and the fact that everyone else was locked down and his friends and admirers couldn’t come visit him was a bit of an added bonus.

David, certainly when he was young, was much more of a traveler. There are Hockneys from all kinds of places, China and the Grand Canyon and Norway near the Arctic Circle. But in Yorkshire he was more fixed to a spot. He was living in a little town and driving out to paint and draw different places in the surrounding countryside. Now he’s confined to a few acres around his house that he can walk.

There’s a contrast between Hockney’s response to the lockdown and your own. He embraces it as an opportunity to ignore distractions, as you say, and look more closely, whereas there’s a sense that you’re just trying to survive this period.

Although I’ve certainly taken note of the fact that one can get more and more out of one’s surroundings, I’m not in the mood to stop traveling. As soon as travel becomes possible again I expect I’ll be off somewhere. My wife and I were going to go to India just about the time lockdown hit, to Mumbai and the Ajanta caves. We’ve got tickets, postponed from pre-lockdown days, to go to Japan this September—but I’m not sure whether we’ll be able to make that trip.

When Hockney’s work from Normandy was shown on the BBC’s website, during the first wave of the pandemic in Britain, it went viral, so to speak. Why do you think it resonated with people so powerfully?

Well, there are a number of elements. One is that David has an amazing power to cut through to a wide public. Simply by releasing a paragraph or two of remarks and some recent iPad images to the BBC, he became a major news story. He was pretty prominent on the front page in most of the British newspapers, instantly, and they were reproducing these images. It had a surprising impact—You wouldn’t expect landscapes or flower studies to spring straight onto the front pages of newspapers.

I suppose the positive quality of them, David’s message to just love life, also came through. That, and the fact that one could find a lot of interest in one’s garden, or the park one was obliged to walk around to get daily exercise. I don’t know what happened in the States, but in Britain we were all told we could only go as far as we could walk from our house in the lockdown. So a lot of people started taking a much closer interest in the local parks. That was one of the government slogans: “Stay local.”

In terms of art as a coping strategy, there’s a quote in the book where he says something to the effect that “stress is worrying about something in the future, but art is now.”

MG: Yes, that’s a very good remark, I thought. David says he loses himself when he’s working, loses the sense of time because he’s concentrating so hard. According to certain psychological theories, that is happiness—losing oneself in a task like that, because you’re not worrying about what may happen in an hour or a week. In David’s case he was concentrating just on what was around him, on a leaf, or a branch, or a blossom, or a shadow on the grass.

He also says that art is the best way to actually see something—that there are all these natural phenomena, like the rain or a sunrise, that can’t be seen properly in a photograph. You have to draw or paint them.

Yes, that’s one of David’s big theoretical positions, that human beings don’t see in the way that a camera does. David doesn’t think the camera is very good at depth perception, for various reasons. It’s partly because most human beings have binocular vision, so we’re seeing from two different points of view. Also, the way the brain organizes vision is through time and informed by all the experiences we’ve had before, so it’s analyzing—we’re not aware of this, but we’re analyzing what we’re looking at on the basis of all the other trees and skies and buildings we’ve seen before. A camera can’t do that. So looking at something is a different experience than taking a photograph of it, and drawing, according to David, is an interpretation of the experience of looking.

His relationship to technology in general, even beyond photography and the older optical devices he’s written about, is so interesting. In recent years he has really embraced the iPad, as you can see from the many drawings made with it in the book.

He’s always been curious about what new machines might provide for an artist such as him, what their visual capabilities are. It’s not just the iPad. For decades he’s been playing around with machines as they came along. There’s a very good series of prints with a color photocopier, in the 1970s and ‘80s, and he did another series using the fax. He was always interested in computer drawing, but he said that until he started playing around with his iPhone in 2009 it had been too slow to use. There was a lag—you’d draw a line and wait five seconds for it to appear on the screen.

He’s having quite a prolific spring this year—another iPad drawing appeared in my inbox yesterday. I talked to him a few days ago and he said he was about ten drawings ahead of his email circle—he sends things out to us almost as he’s doing them. He’s also working on a big project, his own version of the Bayeux Tapestry. It’s going to be exhibited in Paris in the autumn. It’s about 200 feet long, and it moves through the seasons from winter through spring, summer, autumn, and winter again. This January, there was snow on the ground in Normandy for just about an hour and a half. He told me that he was listening to the weather forecast and he was ready for it, and drew it very fast before it melted. That’s the last segment of this continuous picture, which unfolds as you stroll alongside it. He sent out a film of it a few months ago. It’s very striking.

It must be amazing to be on the receiving end of these updates.

Yes, that’s another way David has used technology. He realized quite early on that digital media gave him an opportunity to keep everyone up to date with what he was doing, which he likes. He’s been sending works out on a daily basis, so everyone is up to speed with him.