Sanford Biggers likes to talk about his art as a form of "code-switching," or speaking across multiple social contexts. "The work has to be able to communicate its own being in different languages," he says. "It navigates the world of the collector, but then there's another world of the museum, and of the average person off the street."

About a decade ago, the New York-based artist discovered a rich material for his work, one that was already highly coded: the traditional American patchwork quilt. While doing research for a site-specific project at the Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, he learned that quilts had perhaps been a signaling system for slaves traveling to freedom along the Underground Railroad. The specific pattern on a quilt or the way it was displayed on a porch or fence could, it was thought, provide vital information about safe houses and escape routes.

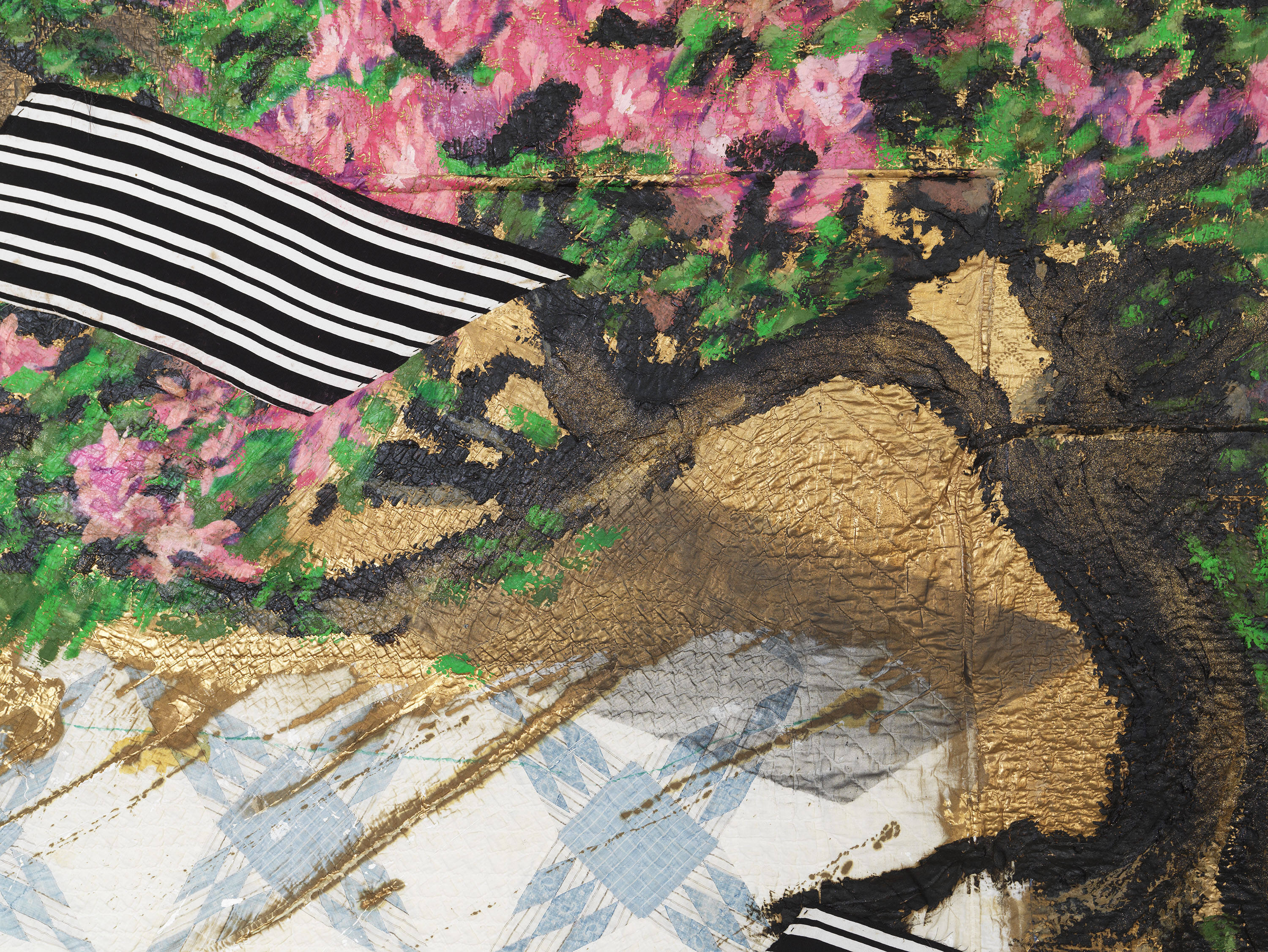

The idea inspired Biggers, who has made many other works in a variety of media about the history of slavery and the Black American experience, to work directly with found antique quilts. For the past decade, in a body of work now called the "Codex" series, he has been painting over them, cutting them up and re-sewing them into new patchworks, and extending them into puzzle-like wall reliefs. And while he may be scrambling their original semiotics in the process, he is also adding new codes of his own—including references to Buddhism and Afro-Futurism, and even actual QR codes that can be scanned by the viewer's phone.

The series is now the focus of a nationally touring solo exhibition, "Sanford Biggers: Codeswitch," which opens at the Bronx Museum on September 9 and is accompanied by a beautiful catalog that delves into some of the history behind the quilts. It will travel to the Museum of African Art in Los Angeles next spring and then the Contemporary Art Center in New Orleans in the fall of 2021. Other quilt works by Biggers and some of his marble sculptures will also be on view at Marianne Boesky in New York, starting later this month, in a show called "Soft Truths."

A few weeks before the opening, Biggers spoke to Artful's Editorial Director about the rich history of the quilts, how it feels to cut up pieces of Americana, and why these abstract-looking works are all about the body.

Karen Rosenberg: As I understand it, your "Codex" series evolved out of a 2009 commission for a church in Philadelphia. What about that site or experience led you to work with quilts?

Sanford Biggers: For a project called Hidden Cities, I was one of the artists invited to reimagine and reinvigorate locations throughout Philadelphia that had gone into disrepair or just hadn't been in the public consciousness for a while. I chose the Mother Bethel Church, which is the oldest black-owned piece of real estate in the country. I was really drawn to the stained glass windows there. I was also considering the Masonic temple in Philadelphia, and looking at their windows and tapestries and patterned rugs. So I wanted to do something about geometry, patterning, and the colors used in some of these architectural elements.

At the Mother Bethel Church there happened to be an exhibition of quilts downstairs. While I was looking at it, I became interested in making some aesthetic connections between the stained glass and the quilts. And then I read the book Hidden in Plain View and I learned from stories passed down from mentors, relatives, and other artists about this fabled story of quilts holding codes for enslaved people who were making the trek on the Underground Railroad from the South to the North—they would use codes on quilts or the way quilts might have been displayed outside of homes as signposts along the journey. That got me to thinking that this vernacular history was a rich and fertile area for exploration. And I started to consider myself a late collaborator, taking antique quilts and then embedding new layers of code directly onto them.

KR: The idea of quilts as codes along the Underground Railroad is apparently disputed by some scholars, according to the catalog for your show, but I think everyone can agree it's such an interesting idea. How do you feel about the possibility that it's fictional?

SB: Well, you know, on some level, if the story persists, then it is real. We live in a time right now where you can see how easily things can be either erased or embedded into our cultural and historical narratives, so with that in mind I look at the quilts as a possibility.

KR: Back in 2002, there was a big and revelatory traveling show of quilts from Gee's Bend, made by self-taught African-American women in rural Alabama, that placed quilts in the context of abstract geometric painting. Did you see that exhibition, or was it an influence on your quilt series?

SB: I did, right around the time I completed my MFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. I was in the painting department, but I was working more with sculpture and performance and installation and sound. But when I saw that Gee's Bend show at the Whitney in New York, in a strange way it sparked my interest in painting again. There was not only an aesthetic rigor and exploration in the quilts themselves but there was also this sort of soft political juxtaposition, seeing these works by Black women in these halls that are usually dominated by white men. And the works held their own.

KR: How do you find the quilts that you work with?

SB: They come from many different sources, but the largest group came from a collector and friend of mine. She was with a group of collectors at my studio in Harlem, and as they were leaving she whispered to me that she used to collect and sell quilts and still had a lot of her inventory just sitting in a closet. She was a descendant of Andrew Jackson, and she had a quilt that went back a couple hundred years.

Through her I got my first large group of quilts, mostly pre-1900 quilts, and I started to really focus on that time frame. Partly because I liked the patina on the quilts, but also because the time frame had more proximity to the stories that I was interested in. I started to find various other resources for getting quilts from that time, ranging from yard sales to internet distributors to word-of-mouth. Sometimes I come to my studio and there will be a box right outside. People don't ever want to throw away a quilt, so they'd rather give it to me to repurpose.

KR: What are some of the qualities that you look for or respond to when you're working with the quilts?

SB: Sometimes I don't have the luxury of choosing them—as I said, sometimes they just show up—so in those cases, I actually work with more of a process bias. I'm using patchwork quilts to make assemblages, paintings, and drawings, and the logic I use is that whatever I'm given I find a way to patchwork it into a new piece. So sometimes I don't get to choose the aesthetic that I begin with—I just choose a way of working with it. Another way I go about it, if I have a choice, is to find certain patterns or color combinations I'm interested in. Sometimes I might find a piece that has a certain degree of wear—it's battered in a certain way, and I know that texture will add something to the final piece.

KR: You mentioned earlier in our conversation that you see yourself as a "late collaborator," working with the makers of the quilts. How does it feel to be working on top of someone's artwork? In the press release for your exhibition you also talk about "embellishing or defacing history"—is there anything difficult or painful to you about this process?

SB: I spend a lot of time with the quilts—it's never a quick exchange. I have a quilt in my possession sometimes for years before it winds up in a piece, because I'm constantly looking at it and waiting for the opportunity to combine it with something else. I do feel that there's a tension in working with these materials that were created by combinations of other people. But there is also a longstanding history of that—sampling in music culture is just one example.

Also, the notion of a patchwork quilt in the first place is that it's a combination of existing pieces. That's why I consider myself a collaborator—I'm following that same chain of procedure in making these works. And a lot of times it's actually recycling, because the quilts are in disrepair and people are not using them in the first place. So I'm actually giving that quilt an opportunity to be resuscitated, placed back on display. I embrace that tension, and I think there's a subversiveness in that act—embellishing or defacing or manipulating Americana.

KR: You have also talked about the idea that quilts, as items of bedding, hold the "memory of the body." These are abstract artworks but they bear traces of the figures they were draped over.

SB: They also have the traces of the hands that made them, whether it was one individual or multiple people. So they're repositories of all of that history. This goes back to your earlier question of how does it feel to work with these already existing artworks—I'm not working just with the aesthetic aspect of them, I'm also working with the traces of all the bodies and human hands that have touched them before. On a formal level they are paintings and drawings and sculptures, but they are also performative objects—bodies were wrapped in them, they were used in the performance of life.

KR: Because the quilts hold traces of the body, and you are cutting them up and recombining them, do they relate in your mind to other works of yours that are commenting on violence toward the body? I'm thinking specifically of the "BAM" series, in which you coat fragments of African sculptures with wax and then fire a gun at them in a powerful reference to police killings of Black Americans. Is there an element of that violence in the quilt works as well?

SB: I don't make just one body of work and I do not use just one tone. And what you're mentioning is that these are two different tones, but they're actually exploring some very similar themes. So there is that very direct violence with the "BAM" pieces, where I'm shooting existing pieces of wood and casting them in bronze, and then you have these quilts which are a soft material but no less a repository of history.

Maybe they are counterpoints—in one you're looking at the horror and it's directly violent, and in the other you're looking at something that seems to be soft but can also be considered a form of cutting and chopping. At the same time it's resuscitated, reconstructed, and repaired, much like the remnants of those wooden pieces are repaired and reconstrued in bronze. There is a cyclical nature to both bodies of work, where it's about destruction and re-creation. That goes back to a Buddhist practice I have that's been very evident in my work for the last twenty years, this continuity of life, death, rebirth, reconstruction, deconstruction.

KR: Going back to the idea of code, and code-switching—can you explain what that concept means to you and how it applies here?

SB: Code-switching is a principle that I consider when making all of my works—even the sculptural pieces, the video and performative pieces. On a more social level, it's when a person adopts certain demeanors or presents themselves in a certain way in response to different situations. For example, if you go to work you present yourself one way, which is very different from the way you present yourself if you're lounging around at home with your friends or family. For women and minorities in this country, code-switching is also a way of sheer survival. In terms of this artwork, I'm acknowledging that the art does exist in the quote-unquote "high" art world but it also is coming from a deep craft tradition.

KR: Code is such an interesting word with a lot of different contexts. One of them is contemporary technology—code is the building block of our whole digital experience. Is this why you added QR codes to some of the works, so that viewers can interact with them with their phones?

SB: I don't necessarily think that these pieces are meant to be totally understood right now in this present moment. I think that the unfolding of an artwork happens over a long period of time, so I look at these works as trans-generational palimpsests. There was the initial code, and then there's the code that I embedded—whether it's aesthetic code or a little QR code. The point is that years, decades, centuries down the line, these could be read by another person who's going to decipher all of this code and may in fact embed another layer of code, so that these are unfolding and part of a long, expanding narrative. I think a good piece of art is one that can change its meaning, one that has the ability to shape-shift.

KR: There is definitely a futuristic streak in your art. In the Philadelphia commission, for instance, you used a map of the stars to connect the Underground Railroad to space exploration.

SB: That was a main impetus for the work, starting to consider Harriet Tubman as an astronaut who was navigating the stars to take people to freedom. She was living and thinking far beyond the era in which she lived. I wanted these works to have the ability to tell a story that affects future generations, much as her story still affects current and future generations.

KR: How did the "Codex" series evolve since those early works in Philadelphia? It seems like more recent pieces become more sculptural, taking on different shapes on the wall or extending into three dimensions with the help of plywood stretchers.

SB: Over the last decade I've been working on the conceptual language of these pieces. Now I'm starting to explore and push the materiality, the formal aspects, in different directions. It's liberating, because I'm no longer trying to construct the narrative. I'm able to actually deconstruct it, in some ways. It reinvigorates the practice for me—just the age-old tradition of really taking the time to know your materials and push and challenge them as they push and challenge me.

KR: You've worked with a lot of different materials and formats over the years. Do you think the quilts are something that's going to stick with you? Are they a kind of signature material now?

SB: Well, I thought I was going to stop using quilts years ago! So I can't predict how long I'll be using them. But for the foreseeable future, they are still teaching me things.

Captions (all works by Sanford Biggers): Harlem Blue, 2013. Antique quilt, additional textile, fabric treated acrylic, spray paint, 88 x 88 in. Chorus for Paul Mooney, 2017. Antique quilt, assorted textiles, acrylic, spray paint, 76 x 76 in. Collection of Brian Ruhl. Incidental Geometry, 2017. Antique quilt, birch plywood, gold leaf, 48h x 17w x 22d in. Collection of Michael Hoeh, New York. Bonsai, 2016. Antique quilt, assorted textiles, spray paint, oil stick, tar, 69 x 93 inches. Reconstruction, 2019. Antique quilt, birch plywood, gold leaf, 38 x 72 x 19 in. Collection of Martin Nesbitt.