From the earliest days of his career, the Swiss-born curator and museum director Hans Ulrich Obrist has been constantly on the move—popping up in a different city each week to visit studios, speak on a panel, or conduct one of his thousands of artist interviews. He came of age riding trains all over Europe to visit artists, once held the title of “head of migratory curation” at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, and likes to compare himself to the itinerant medieval monks who carried their knowledge from one monastery to the next. Travel, for him, is about helping artists and their ideas to circulate in the art world and, eventually, permeate the larger culture—a project he describes with a palpable sense of urgency.

In recent years, as artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries in London, Obrist has also been exploring topics around climate change and looking at ways the art world can become more sustainable while staying international and interconnected. In this process he is, as ever, listening closely to artists, some of whom are thinking beyond the short-term exhibition model and venturing into seemingly unrelated fields such as farming. And at this particular moment, he is now thinking about which rituals to keep from the great social experiment of the pandemic (the Zoom studio visit, in certain circumstances) while celebrating the return to seeing art, and the people who make it, in person.

On a recent call from France, where he had gone to attend the opening of LUMA Arles (he is, among his many other projects, a member of the new arts complex’s artistic committee), Obrist spoke to Artful’s Editorial Director Karen Rosenberg about his love of night trains, the trip he would most like to take, and how we should think about travel in a more environmentally conscious art world.

Karen Rosenberg: You are known as one of the most well- and widely-traveled curators. Why is travel important to you?

Hans Ulrich Obrist: It has to do with the fact that I grew up visiting artist studios, traveling by train. I took the night trains, because I had no money for hotels—I would always spend the night on a train, on the way to the next city. I began with Fischli/Weiss in Switzerland—I met Peter Fischli and David Weiss when I was sixteen, and they really encouraged me to travel. They also introduced me to other artists and gave me their address book. I then took the train to Cologne to see Rosemarie Trockel, Rome to see Alighiero Boetti, and Vienna to see Maria Lassnig. Unfortunately, many of these night trains have disappeared. I think it’s important that they be brought back.

One of the things that you thrive on as a curator is, to use a term that you’ve brought up before, being a “junction-maker”—someone who makes connections between people or ideas, whether that’s in an introduction or an exhibition or event. Do you see a connection between this activity and the physical act of travel?

Yes. Junction-making can mean being in places and introducing people to each other, or bringing people together digitally. Every morning when I wake up I go through lots of rituals: reading Édouard Glissant, and jogging, and writing in a notebook—but one main ritual without which a day really never starts is making an introduction by email. I think about people I could bring together and then send emails saying, “I feel it’s urgent that you meet,” and then these people meet and sometimes something happens. Junction-making also has to do with exhibitions, making junctions between works of art. The term actually comes from the writer J. G. Ballard, who also curated some exhibitions—I never met him, but I did have a long conversation with him by fax and we talked about curating as junction-making.

It goes back to the trips I did as a teenager, because they were almost like an analog internet. When I started, there was no internet. It was 1986, 1987, and the fax was just starting to become a widely used medium. Tim Berners-Lee hadn’t yet invented the World Wide Web, which happened in 1989. So all of these junctions happened—I would just go from city to city and meet artists and then carry that knowledge to the next city. I was very inspired by the migratory monks, who learned everything they could in their monasteries and then would bring that knowledge to the next city.

For example, in 1986 after a visit with Rosemarie Trockel where she told me to not only visit emerging artists of my generation but also to visit pioneering artists of previous generations, I took the night train to Vienna and met many younger artists there. I asked them, “who is an artist from a previous generation who inspires you?” and they all said I needed to meet Maria Lassnig. Maria at that time was showing in Austria but was not really known outside, just in the German-speaking world. I was incredibly mesmerized by her painting. That was a typical act of junction-making—very pre-internet.

Are there people who have been inspirations for your travel? Artists, curators, or perhaps favorite authors who have written on the subject?

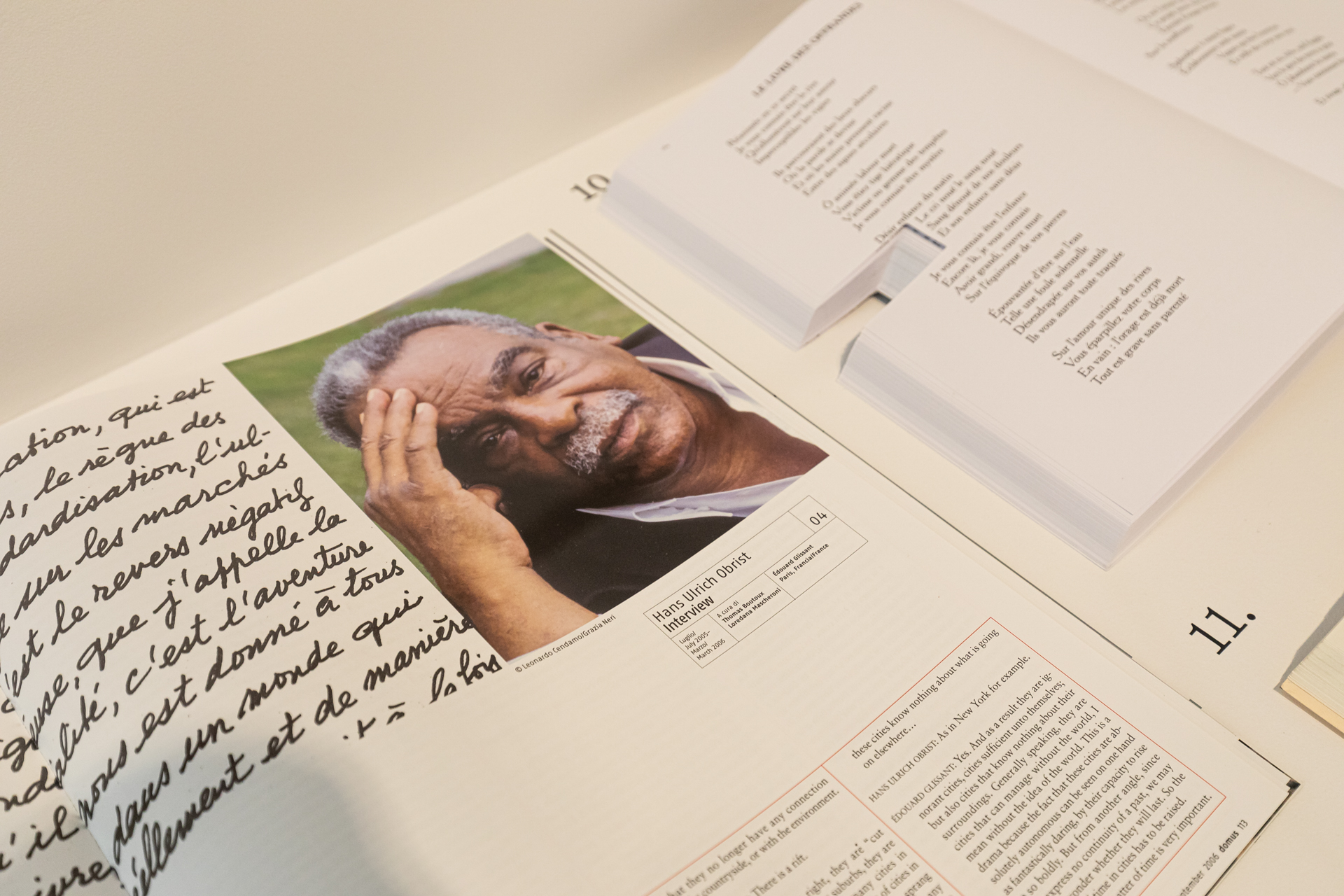

For everything I do, Glissant has been the great inspiration. I’m working on an exhibition for the opening of the LUMA art center in Arles—we are showing all the video interviews I have done with Glissant, and there are nine conversations with him. He was always telling me that we need to think not only about travel to other places, but about travel within the place where we are.

At the Serpentine we just opened a pavilion designed by the architect Sumayya Vally, who envisioned it as a Glissantian “archipelago”—there would be a pavilion in Kensington Gardens but then it would take place in other parts of London, and they would be like islands. This idea of the archipelago has been a big inspiration for me, because it implies that neither each person’s identity nor the collective identity are fixed—that I can change without losing my sense of self. It has a lot to do with the idea of traveling. The archipelago is kind of an antithesis to the absoluteness of Continental thought, and to much thought about globalization.

Sumayya, with this Pavilion, invites travel in London locally. It’s a gesture to decentralize architecture. The whole Pavilion was inspired by neighborhoods like Brixton and Hoxton, which are significant to diasporic communities. Sumayya not only brings the inspiration from these communities into Kensington Gardens, but she also invites us to visit these communities and be in dialogue with them. We need to think more about what it means to travel within our own cities.

During 2020 I started to walk more and more, and it opened up a different experience of the city. I was also inspired by Robert Macfarlane’s book “Landmarks,” where walking opens up the experience of landscapes.

How else did you adjust to a life without travel during the pandemic, and how did you stay connected to artists?

How else did you adjust to a life without travel during the pandemic, and how did you stay connected to artists?

It was challenging to be connected to artists at the beginning, because during the lockdown it wasn’t even possible to visit artists within London. It took me a little bit of time to figure out that studio visits can also happen virtually, by Zoom, even if it’s far from the engagement of the in-person studio visit. I always say, a Zoom studio visit is a prelude to a later studio visit in person—a lot of things are missing. But it’s a great way to meet new artists and revisit artists you have already met.

It’s also a more decentralized activity, in a way—I made many studio visits with artists in Asia, the U.S., Africa, Australia. For example, I had a Zoom visit with the pioneering artists Jae and Wadsworth Jarrell, who had been instrumental in the 1960s as protagonists of the AfriCOBRA movement in Chicago. I had always wanted to visit them, but it was difficult for me because they left Chicago a long time ago and now live in Cleveland. We met by Zoom and it was their first Zoom call ever.

As you interacted with artists, how did you see the pandemic and its restrictions impacting them? Is there any defining quality that you observed in the art being made under these conditions?

It’s difficult to generalize! There is more introspection and also more connection between art and poetry, as shown in an exhibition I curated with Lemn Sissay, "Poet Slash Artist," at the Manchester International Festival this summer. But one thing I saw was that there was so much drawing going on in the period of the lockdown. One could make a quite excellent exhibition of the drawings created then. Many artists couldn’t go to the studio, and for a lot of artists that led to making drawings. You can make drawings without assistants, without big spaces. It can happen anywhere. I’ve seen amazing new bodies of drawing. My partner, the artist Koo Jeong A, created hundreds of new drawings during the lockdown. I recently had a studio visit with Annette Messager, who also created hundreds of new drawings during the lockdown.

One thing that has become more important is the question of the local, and I think that’s something you can see in a lot of practices. The philosopher Bernard Stiegler, who passed away last year, told me that we have to be local but we should not be localists. That’s something which is very Glissantian, because Glissant always said that it’s important to be rooted and we need to think about the local, but this idea of being local or rooted is only important as long as it does not lead to the exclusion of other people’s roots. Then it becomes very dangerous—it leads to nationalism, lack of tolerance, all these things we observed during the Covid crisis.

As the filmmaker and thinker Manthia Diawara says, we can learn from Glissant that we need to be local but not localists, to celebrate roots that extend elsewhere and are not singular. That’s quite an urgent point, because I think there is a danger of new nationalism and new localism appearing at this point in time.

At the Serpentine, you’ve been a big advocate for more awareness of climate change and more environmental responsibility from art institutions. As the art world emerges from the pandemic, how can we reintroduce travel more sustainably?

At the Serpentine, you’ve been a big advocate for more awareness of climate change and more environmental responsibility from art institutions. As the art world emerges from the pandemic, how can we reintroduce travel more sustainably?

It’s important to have slower travel. I already mentioned the train—we need a movement to reintroduce night trains, and to introduce them in places they have not existed. One further characteristic of slower travel is to stay for lengthier periods of time if long distance trips are necessary, a longer engagement with the condition of a specific place.

We’ve been working a lot at the Serpentine on “Back to Earth,” which is our environmental program—it’s a long-term focus with many artist campaigns. This project is about going beyond the short term, to longer duration projects. As Roman Krzarnic shows in his excellent book The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World it’s important to go beyond the short termism of event culture.

I have also noticed that artists have started to take an interest in more long-duration thought, going beyond the idea of an event and creating things which can grow over years. For example, Precious Okoyomon had an exhibition at the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt that was closed during the lockdown, and the vegetation in it kept growing in the museum. Now they are creating a very long-term project—it’s not an exhibition; it’s basically a garden in Aspen. When an artist would rather do a garden than an exhibition, that is interesting. Also, a number of artists at the moment are interested in farming as an artistic project. Otobong Nkanga, for example has a farming project in Nigeria. These are long-duration projects—they’re not just events.

The revival of public art has also been very strong. I have been writing during the lockdown about the Roosevelt plan and the whole idea of the New Deal. There was a lot of focus through that on public art, and we can see very clearly now that a lot artists have the desire not only to do exhibitions but also to engage with longer-terms projects in public art. Very often these projects connect to many different communities. For example, Koo Jeong A’s skateboard parks can be seen as artworks but they are being used by skateboarders. Artists doing more long-duration and public art projects, going beyond the short-term format of exhibitions—I think we must learn from this phenomenon, and institutions need to think about how they can answer to it.

What was the first trip you took after the lockdowns, and how did it feel to be back on the road?

I went to Paris to see exhibitions and go into artists studios—not Zoom but real, live studio visits, for the first time in a long, long time. In Paris I saw Etel Adnan and Annette Messager. I also went to see Anne Imhof at the Palais de Tokyo and went from there to Arles to install the show of my Glissant archive at LUMA. It was an amazing experience to be with art again. I had been missing art so much.

Looking ahead, what is your next big trip? And in the spirit of one of your favorite questions from your artist interviews: Do you have any unrealized plans for travel?

I don’t have any long-distance trips planned right now but I look forward to other trips in Europe, many by night train. I do have an unrealized dream for a trip. Glissant wanted to build a museum in Martinique, which he told me would help us to look from a utopian point at all the world’s cultures. We had been planning to go together by boat, because he would always travel by boat to Martinique, and that trip remained unrealized when he passed away. I hope one day to be able to make that trip. I’d like to do it with Diawara, who is a great Glissant scholar. He managed to go on that boat trip with Glissant, from Europe to Martinique, and made an amazing film of it. I’d love to do that trip one day, because I promised Glissant I would visit Martinique.

I have been asking so many artists about unrealized projects, and have cataloged about 2,000 answers. I always thought it would be really interesting to do—not an exhibition, because that would again be too short-term—but a long-term archive presentation, a building where all these unrealized projects would be shown and awareness would be created for them. Maybe then the projects will be realized.