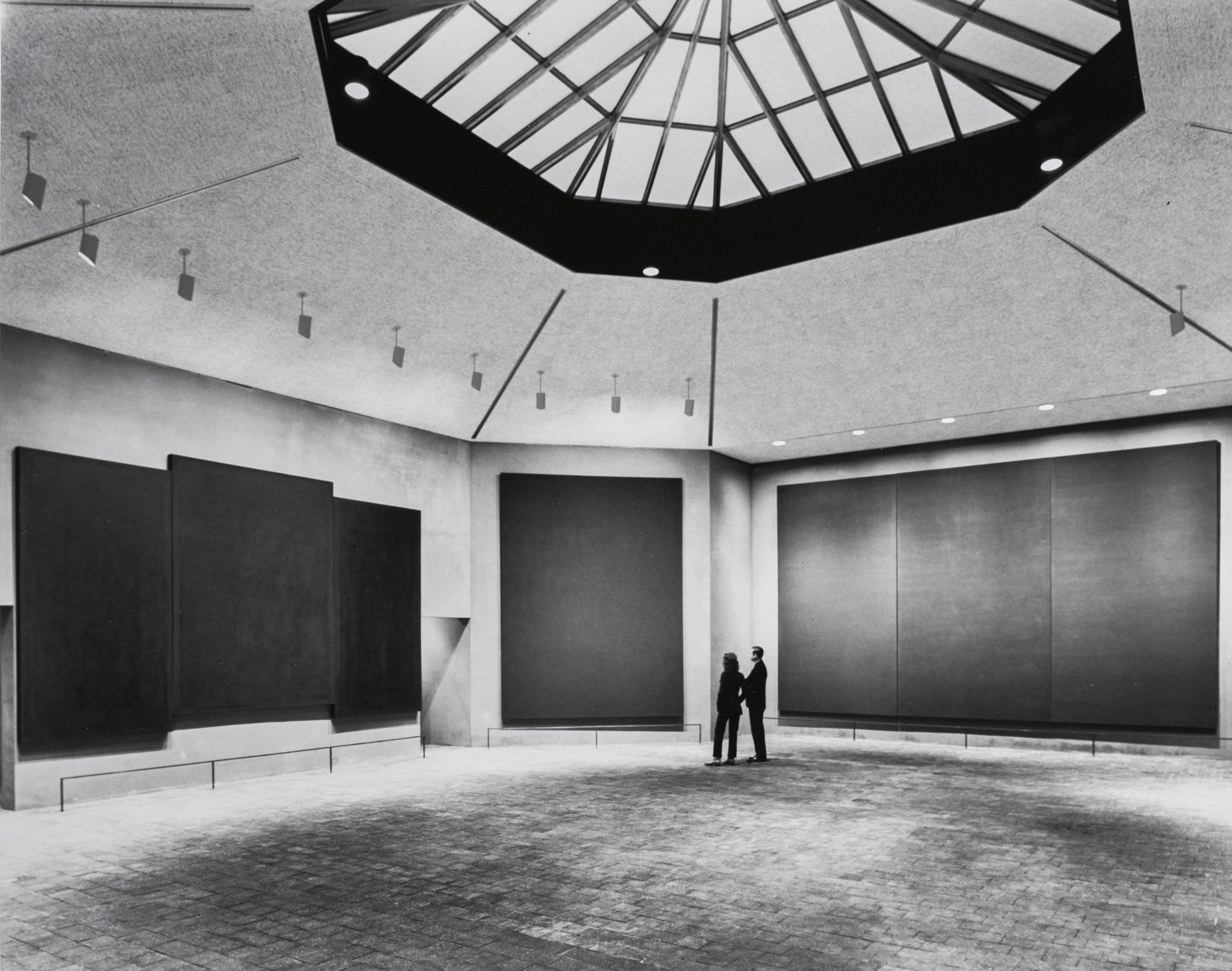

Since 1971, the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas has drawn seekers of aesthetic and spiritual experiences from all over the world. Over the years, however, a series of technical issues prevented the non-denominational refuge, commissioned by the de Menil family of art collectors and constructed around an octagonal installation of paintings by Mark Rothko, from functioning exactly as its creators envisioned.

One problem was present from the beginning. Rothko had never traveled to Houston when he made the paintings, which came to life in a carriage house on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, and the intensity of the Southern sun threatened to overwhelm his dusky canvases upon their installation; to compensate, a baffle was inserted in the chapel's skylight. It was an imperfect solution, even after two updates. Meanwhile, the number of visitors to the chapel increased year after year; more space was needed to process them. And the event program—central to the chapel's social justice mission—was growing to the point that set-up time was frequently interrupting the contemplative experience.

A few years ago, with its 50th anniversary approaching, the chapel announced an ambitious two-part restoration and expansion plan called "Open Spaces." The firm Architecture Research Office, the lighting designer George Sexton Associates, and the landscape architect Nelson Byrd Woltz, all working closely with the artist's son Christopher Rothko, have been transforming the chapel's lighting and architecture and redesigning the surrounding campus; eventually, it will include a program house and more public space for meditation. The first phase of the plan was completed last summer, and after some pandemic-related delays the chapel is now open again to the public (with timed ticketing).

"We use the word restoration for this project, not renovation," says the Rothko Chapel's Executive Director, David Leslie. "It's a very important word, because embedded in all of this is looking backward to the original intent."

Architect Adam Yarinsky of ARO echoes that statement. "A lot of our work has been recalibrating the light to support Rothko's original intention, which was to give viewers this quality of being immersed in daylight," he says. "The experience had been diminished over time by so many incremental decisions. Our goal was to restore the sense of awe that visitors feel."

His colleague Stephen Cassell adds, "The light was so flat because of those plugs that the space didn't have a shape to it. The quality of light is so different now—you're going to read a lot more depth into the paintings."

In addition to working with George Sexton on a new digital lighting system, the architects made substantial changes to the chapel's foyer. They enlarged it and darkened it, to create more of a transition for visitors entering the chapel from the harsh sunlight outside; there is now room to pause and let your eyes adjust. They also improved the sound inside the chapel, adding acoustically absorbing plaster to help ensure a quiet, focused visit.

These changes may sound subtle, but they make it possible, for the first time, to have the slowly unfolding experience Rothko sought. "You don't walk in, look at the murals and walk out—you really have to spend time with them," says Christopher Rothko. "It's almost like he stains the canvases with paint rather than painting them. The canvases are doing the same thing to you, seeping into your pores. It's an osmotic process."

Another goal of the restoration project has been to reinforce the relationship between the chapel building and its surrounding landscape, particularly with respect to the Barnett Newman sculpture, Broken Obelisk (1969), that sits in a reflecting pool nearby. The de Menil family dedicated the sculpture to the legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., in a 1971 ceremony contemporaneous with the dedication of the chapel, and emphasized the dialogue between the two projects—"an interplay between contemplation and action," in Leslie's words.

To that end, the architects and landscape designers replaced a bamboo enclosure around the reflecting pool with more dense-looking walls of holly that create a more defined space. They also introduced a grove of river birch trees to one side and added benches, giving visitors a shady spot to rest. Subsequent phases of the revamp will open up even more space for meditation and for public programming, mainly by removing old bungalows on the north campus.

In the meantime, the chapel stands ready to welcome anyone looking for a place to commune with art and reflect on, or perhaps escape from, this tumultuous year. "The unfortunate thing about the pandemic is that the chapel is needed more than ever," says Leslie. "To have a space to get out of the house, to be whole again." Or as Christopher Rothko puts it, "People need both a place that's safe and a place that's outside of their homes. When, ever, was there a greater need for a feeling of sanctuary?"

Captions:

1) The Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas, 1971. Photo: Hickey-Robertson.

2) The Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas, 2015. Photo: BEND Productions

3) The Rothko Chapel interior at dusk, 2020. © Elizabeth Felicella

4) The Rothko Chapel plaza, 2020. © Elizabeth Felicella