Andy Warhol was enough of a jet-setter, particularly late in his career, that he once appeared in a television advertisement for Braniff Airlines. But the idea of Warhol as a traveler still feels a bit counterintuitive, given his status as a die-hard New Yorker, his associations with generic American supermarket fare, and his reputation, at the Factory and elsewhere, for turning himself into a destination that others would seek out.

As a substantial new biography of the artist by Blake Gopnik makes clear, however, Warhol really appreciated travel and was in many ways defined by it. The Warhol of the book is less American, and less Pop, than the one we know. Travel nurtured his obsession with food of all kinds—not just canned soup and hamburgers, but also haute cuisine and Japanese omakase—and his interests in all kinds of visual expression, including opera and ballet. It also reinforced his identity, as a gay man and member of multiple bohemian subcultures, and the feeling of vulnerability that went with it whenever he left New York.

"Travel is vitally important to Warhol, because a lot of his life was about getting away from Pittsburgh," Gopnik says. "Distance between one place and another really shaped Warhol, and his distance from mainstream culture is one of the most important things you have to understand about him. Both literal and metaphorical travel mattered a huge amount to him."

In a recent conversation, Gopnik spoke to Artful about the specific trips and destinations that shaped Warhol's life and art.

Around the world, 1956

Although we now travel around the world relatively blithely, 1956 was still the very early days of international air travel. So taking an airplane all the way around the world was a tremendous adventure. Warhol—and his friend or boyfriend, depending on how you want to look at it, Charles Lisanby—actually took one of the longest flights that was possible at the time, to get from the West Coast all the way to Asia.

The trip gave him his first exposure to art in situ, to monuments. He went to Rome and saw the Baths of Caracalla; he went to Florence and saw the Baptistry. He really got to experience the art of the world in person, in a way he hadn't before and in a way that few people did at the time. It wasn't normal for artists to have that kind of international exposure the way they do now.

Warhol is so firmly associated in our minds with American-ness and the American experience, and of course American Pop Art, that we have lost track of his interest in other cultures. Once he came back from his trip, he was fascinated by Japanese restaurants and Japanese food. He went to the first Japanese restaurant in New York, which became a hangout of his. Throughout his life, he was fascinated by the food of other cultures. So it wasn't just that he traveled to look at art, or get new grist for his artistic mill. He was interested in culture in the very largest sense. And that's important for understanding his Pop Art as well. It wasn't only about art, in any normal sense. It was about grasping at cultures of all kinds.

Los Angeles, 1963

Warhol's road trip from New York to Los Angeles [with Wynn Chamberlain, Gerard Malanga, and Taylor Mead] is often billed as a Pop trip, through the American landscape of billboards and restaurants in the shape of hamburgers. But it's important to recognize that the end goal of that trip was not Pop at all. It was about going to have his second solo show at the Ferus gallery, which was a very high art experience, and getting to see the great Marcel Duchamp retrospective in Pasadena. Warhol, when it came time to choosing where he was going to eat, did not in fact want to go to the diners and the hamburger-shaped restaurants along the way. He ate in very middlebrow steakhouses that he could pay for by credit card.

The arrival in L.A. mattered more than the trip across the continent, which was a very quick trip—they drove as fast as they possibly could, at great danger to themselves.

And then, once they arrive, they make Warhol's spoof of a Tarzan movie, with Taylor Mead, ridiculously, as Tarzan. It was shot in a lot of the tourist spots in L.A.: the merry-go-round in Santa Monica, the Watts Towers, the famous hotels in Beverly Hills. It's a kind of travelogue to this strange, jungle-like place, this deeply "other" environment that Warhol settles into.

Paris, 1965

Warhol went to Paris again and again throughout his life—it's one of the few places that's really important to him. This was his first trip there. In the 1960s and '50s Paris was really a magical place in the American psyche, so showing up in Paris with his entourage [Gerard Malanga, Edie Sedgwick, and Chuck Wein] mattered a great deal to him. It was the very beginning of his Francophilia, although he'd already been making French food before that.

Ileana Sonnabend's gallery, where he was opening an exhibition of his "Flowers" paintings, was also very important to encouraging European interest in his art. His work was always better received in Europe than in the United States, both in terms of sales and critical interest. The Europeans, and the French in particular, saw his Pop art as caustic and critical and quite left-wing. Americans were never quite able to see that side of his work. So the trip to Paris was very important in affirming for him that he was onto something important and mysterious.

Touring the Upper Midwest with the Velvet Underground, 1966

Warhol, over the course of his life, managed to have all of the archetypal travel experiences that you can have. He had the around-the-world tour. He had the cross-country road trip. He had the Parisian bohemian experience. And then he had this low-end travel, as a roadie with a rock band. It sounds kind of unpleasant, with lots and lots of people in an R.V.. But he wanted to save money, so that's the experience that he gave himself and the entire Velvet Underground band. And maybe it was an experience that he needed to have. He was certainly interested in exploring all the iconic experiences that you could imagine, from the very lowest to the very highest.

I think it's important to understand all of Warhol's trips as moments where he leaves the safety of New York's bohemian culture. Traveling across the country as a gay man was a very brave thing to do, frankly. It was risky: being alternative, being bohemian, being gay, anywhere really except New York. Warhol and his entourage were at threat at various moments in those road trips. There's a famous moment when the R.V. breaks down and the other roadies don't want Warhol going out to talk to the cops, because they're afraid that bad things will happen.

Western Europe, 1970s

The only serious vacation Warhol took was that around-the-world trip in 1956. After that, most of his trips had a work agenda. He rarely if ever traveled for fun. He rarely did anything for fun. All the fun he had was part of the work of being Andy Warhol the artist. So by the 1970s, and certainly into the '80s, when he's traveling in Europe it's mostly in order to find portrait sitters. And that just becomes part of what it was for him to go to Europe. He goes to Paris a few times, Lucerne, London, Rome.

He made sure that the travel itself was as high-end as possible. He was eating caviar in really fine hotel rooms. He rented a villa outside Rome and hired an Italian chef. Restaurants mattered a great deal to him—he was an early foodie, which goes against his Pop image as a consumer of Campbell's soup. I've seen the receipts for his meals at Maxime's in Paris and at every other fancy restaurant you can imagine. We know he took the Concorde not only because the tickets survive, but also because all of the stuff he pilfered from the Concorde survived. The Concorde had quite nice cutlery, and a lot of it is in Andy Warhol's archive! He had a taste for luxury by that point. And you can't blame him, because he was working so hard and hunting for portrait patrons isn't that much fun, especially when a lot of them are turning you down.

.%20Courtesy%20Duane%20Michals%20and%20DC%20Moore%20Gallery%2C%20New%20York%2C%20%C2%A9%202018%20Duane%20Michals.jpg)

China, 1982

Warhol had gone to Hong Kong in 1956, but he also went to mainland China in 1982, a decade after he made his paintings of Mao. It's hard to remember how different China was then from what it is now—it was seen as a deeply exotic place. And Warhol was always much further to the left than people realize. I think he had a certain sympathy, at least in principle, for the goals of a Socialist or even Communist revolution, even though it was obvious to him that China was not in any real sense a Communist state. It was certainly no Socialist paradise. But I think he was interested in the idea, and that's one of the reasons that trip to China mattered more to him than maybe we realize. Lots of photographs survive from it—he was keen on documenting the peculiarity of life in China in the 1980s.

Milan, 1987

Warhol's final trip was to Milan, in early 1987, for one of the best-received shows he ever had. Alexander Iolas, the great dealer, had arranged for an exhibition of Warhol's Last Supper paintings to be shown in a bank that was next door to Leonardo's own Last Supper. Warhol is already terribly ill—his gallbladder is about to burst and is already deeply infected at that point—but he's a trooper. He goes to the opera, La Scala, and does his best to have a good time, but he's sick as a dog. The crowds for his Last Supper paintings were just insane; about 5000 people showed up when they expected maybe 500. All the Italian press was there from across the Italian peninsula. It was a victory for him, a reprise of the "Andymania" from his first museum show in 1965 at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, and yet he's too sick to really appreciate it. Then he comes home and he's dead a month later. His last trip should have been a wonderful celebration, but he couldn't really enjoy it.

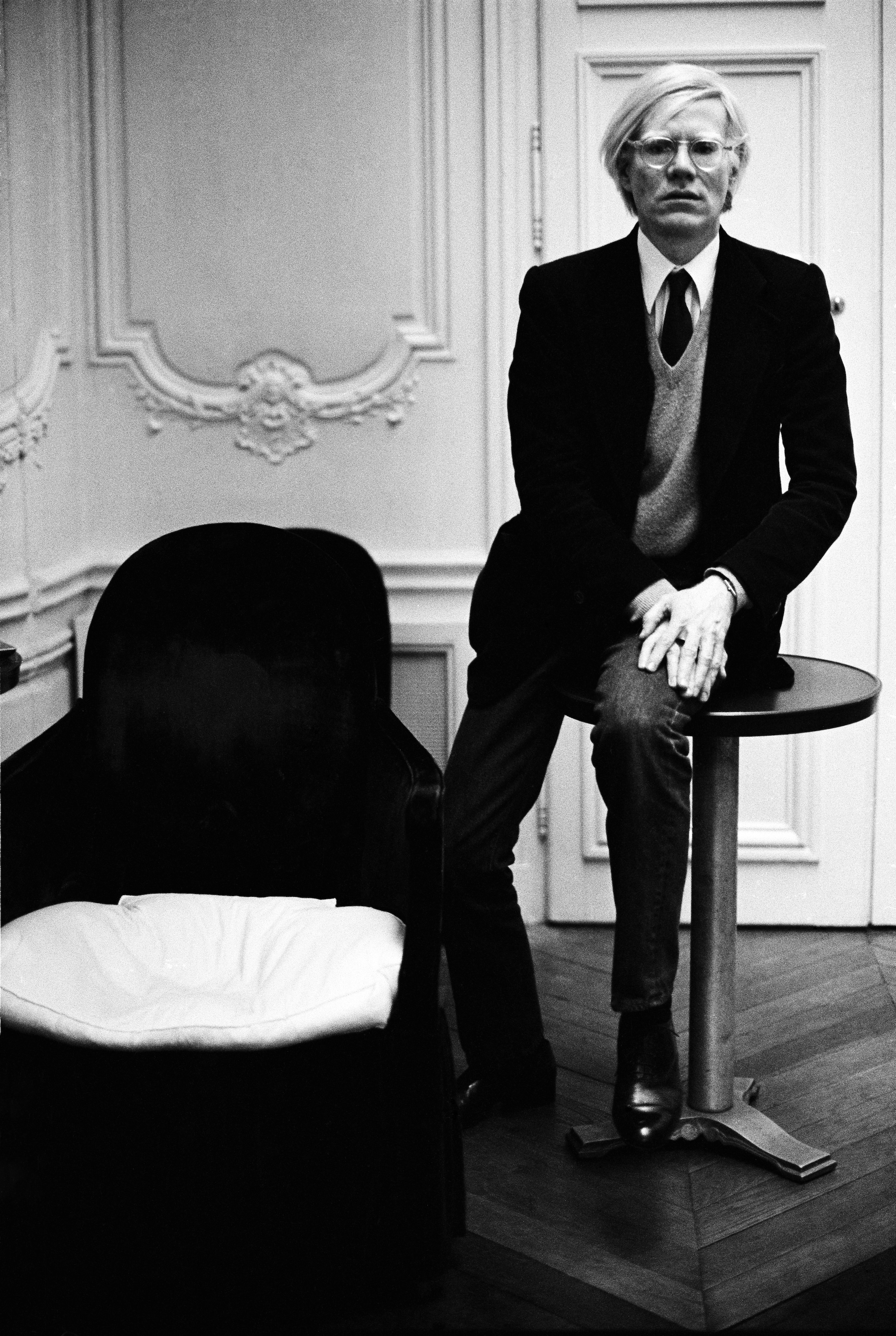

Captions, top to bottom: "Andy Warhol—Paris Apartment," 1980. Photograph by Michael Childers. Duane Michals, "Andy Warhol" (c. 1974). Courtesy Duane Michals and DC Moore Gallery, New York, © 2018 Duane Michals.