Anni Albers and her husband and fellow artist, Josef Albers, met at the legendary Bauhaus in Weimar, Germany and became influential teachers there before emigrating to the United States, where they nurtured students at Black Mountain College and Yale University. Their ideas about modern art, however, were profoundly shaped by a different country. Between 1935 and 1967, they made no less than thirteen trips to Mexico and encountered art and artifacts that changed the way they thought about material, color, and abstraction.

A few years ago, an exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York explored Mexico's influence on Josef Albers. Now "Passerby 04: Anni Albers," at Museo Jumex in Mexico City (through February 28), makes clear that Anni Albers deserves the same treatment. Meanwhile, the new book Anni & Josef Albers: Equal and Unequal by the Josef & Anni Albers Foundation director Nicholas Fox Weber (out this month from Phaidon) also sheds light on the artists' travels in Mexico and the objects they acquired there, as well as some of the cultural luminaries they befriended on their trips.

"Most writing and research that has been done so far is on Josef Albers. I thought there was a need to focus on Anni, on her practice as an artist and designer and scholar," says Catalina Lozano, the curator of the Jumex show (which is part of the museum's "Passerby" series of exhibitions on the exchanges between artists in Mexico and outside the country).

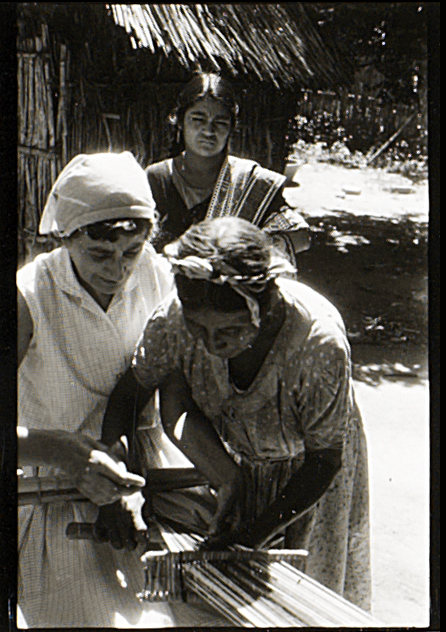

As a textile artist, Anni Albers was drawn to the traditional weaving styles and techniques of Mexico's indigenous artists and incorporated them directly into her own work and teaching. In Oaxaca, local weavers taught her to use the Peruvian back strap loom, a simple and highly portable device that nonetheless enabled patterns of astonishing complexity.

Albers was so enamored of the back strap loom that she used it to teach her students at Black Mountain College. As she told an interviewer for the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, "the Peruvian back strap loom has embedded in it everything that a high power machine loom today has." In general, she approached the indigenous art of Mexico with an appreciation for its technical sophistication and endurance. As Lozano says, "She understood herself as part of this long tradition. She didn't see herself as the culmination or as more advanced, but as another weaver."

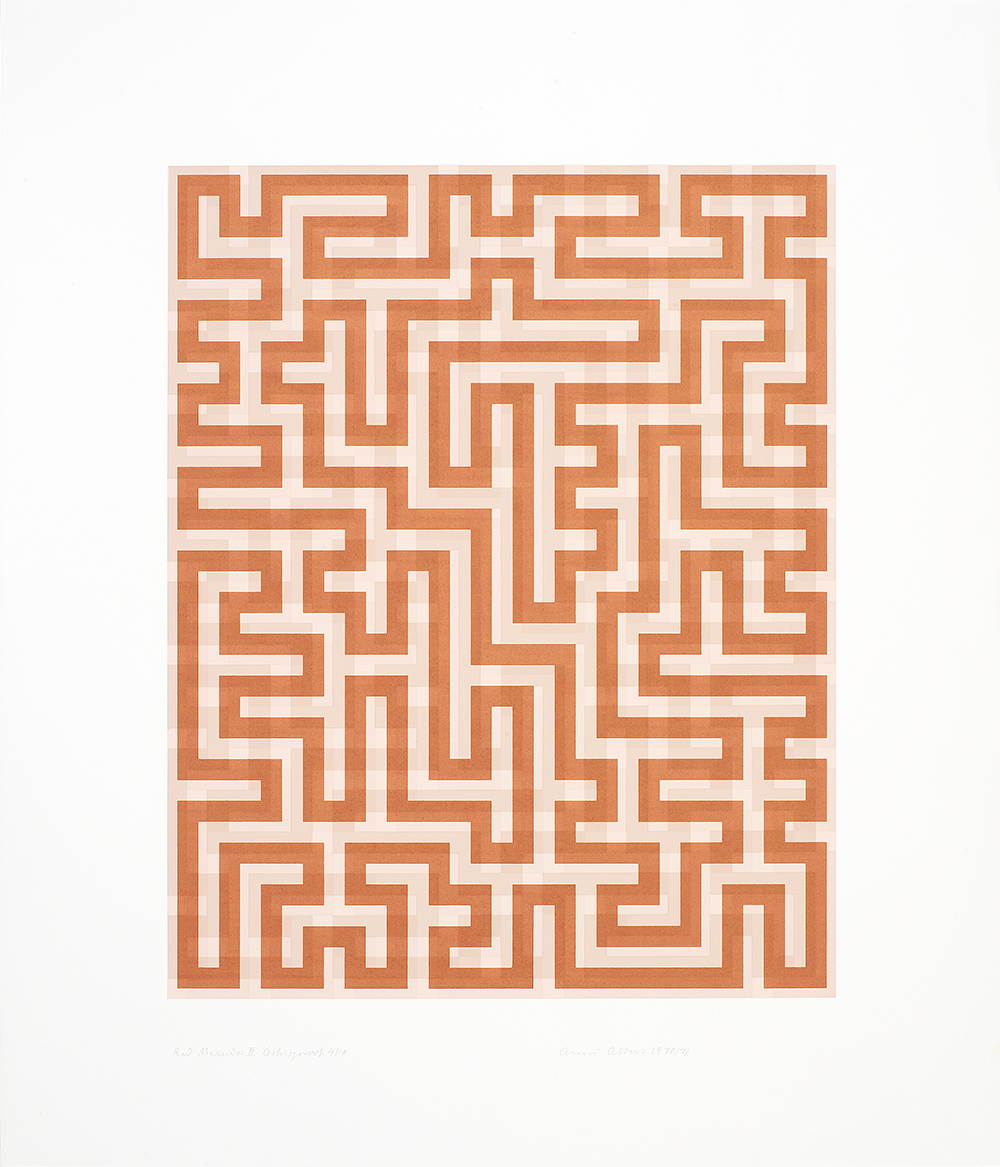

Some of Albers's own textiles refer directly to her lessons from Mexico. Monte Albán (1936) nods, in both its title and its motifs derived from Zapotec architecture, to an important archeological site she visited. Ancient Writing (also 1936) takes inspiration from the idea that pre-Columbians weavers encoded messages in sequences of knots. Later in her career Albers also made a large wall hanging for the lobby of the Hotel Camino Real in Mexico City, Camino Real (1968), which was lost in the 1980s and only recently rediscovered in the hotel's vaults. This work, which features an intricate motif of triangles, was exhibited last year at the David Zwirner gallery in New York and is the subject of a new book published by the gallery.

On her trips to Mexico Albers also developed a passion for pre-Columbian miniatures, and along with her husband amassed an impressive collection of more than 1,000 of them—now part of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, and the subject of a 2017 show at the Yale University Art Gallery. She referred to these diminutive stone and ceramic figures as "small-great objects," and admired that they could be easily held in the hand. In his Phaidon book, Fox Weber details the first miniature the Alberses acquired, a three-inch ceramic figure of a woman in a headdress, an impulse purchase from a little boy who had been trying to sell them his baby goat.

"She was very interested in simple yet complex objects," says Lozano. "I don't think that she would have been impressed by things that were bigger or shinier." Although she admired the jewelry that had been discovered at Monte Albán, it was not the precious metals and stones she liked as much as the ingenious use of those materials. In a 1942 lecture at Black Mountain College, she recalled: "These objects of gold and pearls, of jade, rock-crystal, and shells, made about 1000 years ago, are of such surprising beauty in unusual combinations of materials that we became aware of the strange limitations in materials commonly used for jewels today." With a student who had accompanied her in Mexico, Alex Reed, she went on to make a collection of jewelry using washers, bobby pins, and other dime-store items.

Overall, the Alberses' travels in Mexico informed their understanding of art history and their own place in it. Where other Western artists of their era tended to see ancient art as "primitive," the Alberses approached it with humility and a sense of continuity. "In the case of Anni especially, but with Josef too, they never looked at these objects in a paternalistic way," Lozano says. "They admired the complexity."