The Moroccan-French artist Yto Barrada is known for her interest in maps and borders and their sometimes awkward relationship to human experience. In her series of photographs A Life Full of Holes (1998-2004), she explored the lives of African migrants who crossed the Strait of Gibraltar to live in Tangier. In a more recent multimedia work, Tree Identification for Beginners (2017), she took a critical look at a trip her mother had taken to the United States in 1966, as a 23 year-old Moroccan student invited by the State Department to tour the country with other “Young African Leaders” at a time of national unrest.

Now, as the latest artist selected by the Museum of Modern Art to participate in its “Artist’s Choice” series, Barrada is testing another kind of boundary: the one that separates the neurotypical from the neurodiverse. Her show centers on the research of the French social worker Fernand Deligny (1913-1966), who experimented with a new way of communicating with nonverbal autistic children and whose work has become influential in artistic-literary circles as well as in the field of autism studies.

Deligny and his volunteers lived with the children in a rural setting, allowing them to move freely between fixed stations of adult supervision and using drawing to map their movements. “The goal was to create a common space with children who would have otherwise spent their lives locked up in state-run psychiatric asylums,” Barrada wrote in an email to Artful. “Deligny's space offered a collectively run nonviolent alternative to these institutions, with freedom for the children, though of course there was significant precarity.”

The show title, “Yto Barrada—A Raft,” refers to the term Deligny used to distinguish his project from the “cargo ship” of the institution. “You know how a raft is made: you have tree trunks bound together quite loosely, so that when a sheet of water hits, the water passes through the gaps between the trunks,” he wrote in 1978. “The bond must be loose enough, but without losing hold.”

Barrada first became interested in Deligny through friends from her student days at the Sorbonne, Sandra Alvarez de Toledo and Anaïs Masson, who went on to found the publishing house L’Arachneen and, in 2007, reissued some of Deligny’s books as a single volume. “Since then there has been a great deal of renewed interest in his works across disciplines of thinkers and artists,” Barrada said in her email. For the MoMA show she has collaborated closely with Alvarez de Toledo and Masson, as well as a translator, Robin Mackay, who has given new English subtitles to a documentary on Deligny by Renaud Victor (Ce gamin, lá, 1976.)

The attention to Deligny can be seen as just one example of the art world’s developing interest in social work and related fields. The list of Turner prize nominations announced last week, which consists entirely of artist collectives, includes a coalition of neurodiverse artists and activists known as Project Art Works.

Art made, or inspired, by those with intellectual or developmental disabilities is not new to the walls of MoMA, or other modern and contemporary art museums that have exhibited “Outsider Art.” However, much of that history is centered on art made in an institutional setting, or, like Jean Dubuffet’s definition of “art brut,” commingles artists with autism spectrum diagnoses with others who have psychiatric conditions or are simply self-taught.

In her show (which is accompanied by a MoMA Virtual Cinema program that runs from June 3-22, and coincides with an exhibition of her work at Pace in East Hampton through May 23), Barrada connects Deligny’s ideas to a wide variety of contemporary artworks—many by artists who are not normally associated with neurodiversity but who share the social worker’s interest in mapping movements and gestures or living “outside language.”

“In MoMA's collection, we tried to look for inventions, forms, performances, gestures, where Deligny's critique of language echoes,” Barrada explained. “There are many ways to associate works from the collection to Deligny's ideas, and we looked at a group that would chart new geographies of what it means to be human.”

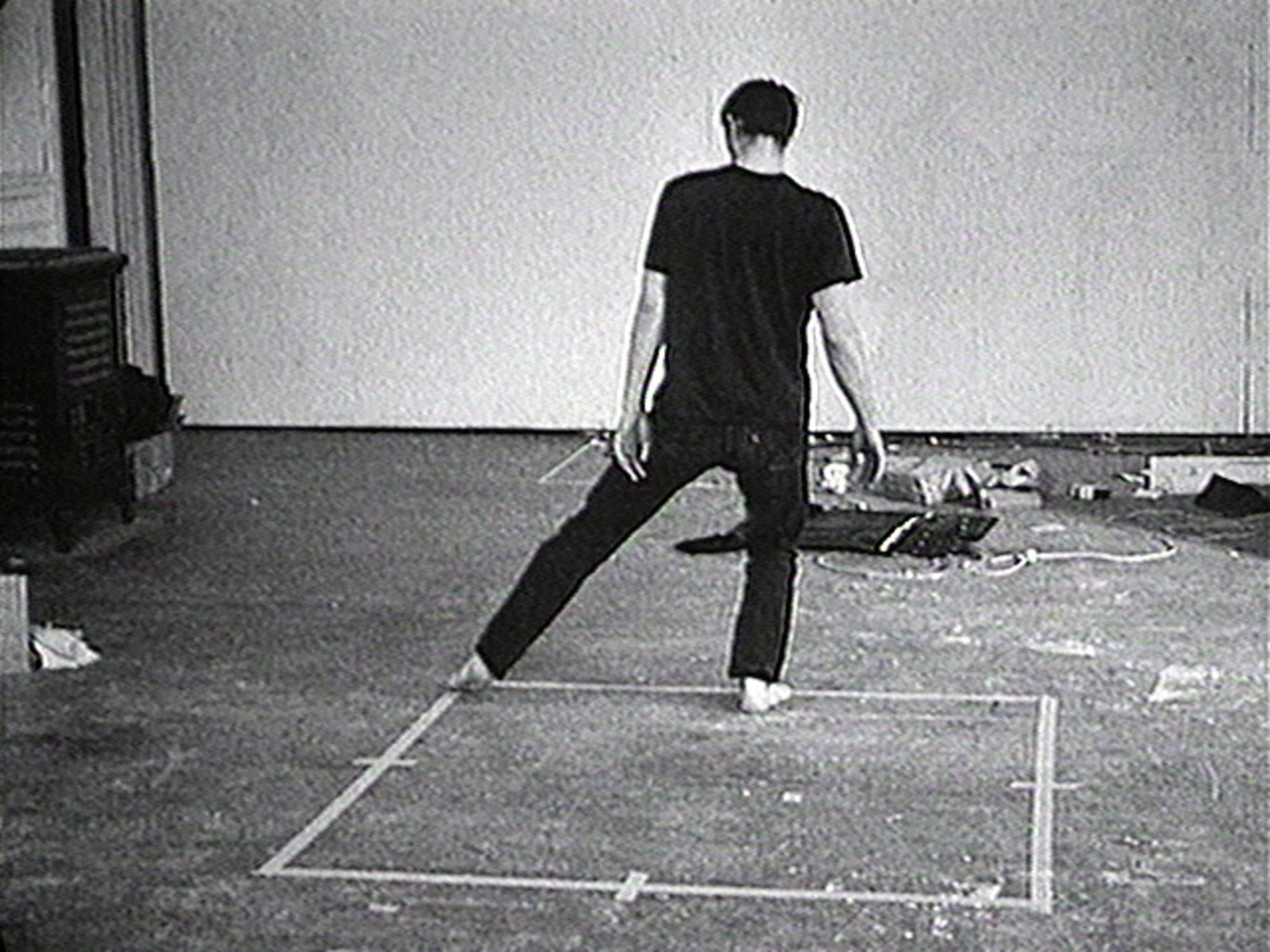

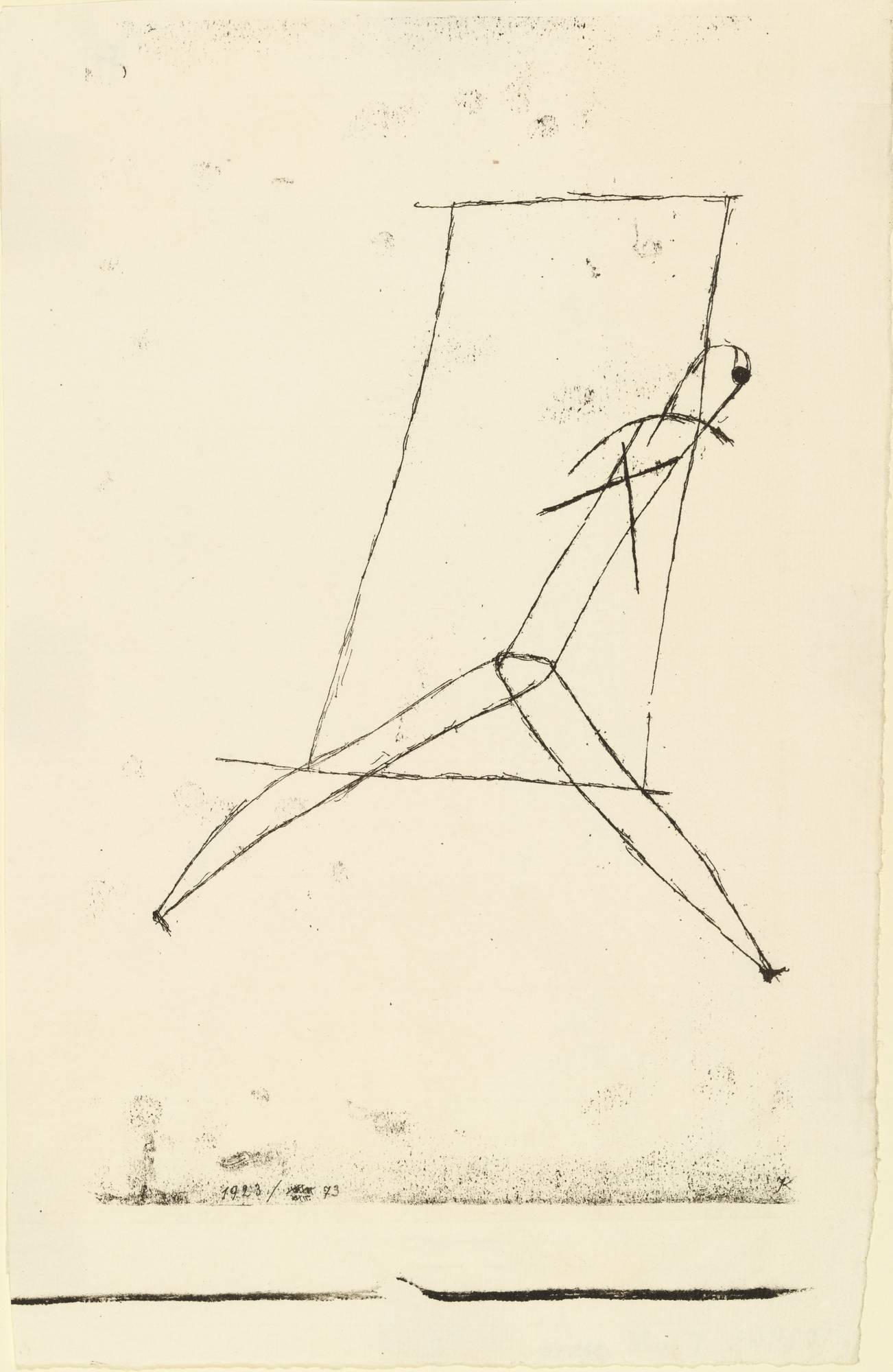

In two videos from the late 1960s, Bruce Nauman explores the perimeter of a square outlined on the floor with methodical, repetitive steps. The arcs and loops in a large performative drawing by the dancer and choreographer Trisha Brown record her movements across the paper.

Sheets of paper covered with tiny circles, by a child identified as Janmari who was living in Deligny’s “raft,” connect visually and experientially to Michael Snow and Joyce Wieland’s mesmerizing film of water dripping onto a plate.

A sense of communal living, meanwhile, comes across in a 1971 film that shows the artist Gordon Matta-Clark building a sculpture from scavenged items under the Brooklyn Bridge with the help of passers-by.

Exhibited alongside these works are several of the map-like drawings Deligny and his colleagues made in order to trace the paths of the children in their care. They include both meandering lines and little symbols that represent various actions taken by the children. The notations, and the principles behind them, are explained in detailed labels which incorporate translated snippets of Deligny’s writing. “His language is powerful, beautiful; it's poetry,” says Barrada. “The way he writes is very slippery—you think you grasp it and it sidesteps.”

Barrada has also included some of her own works in the show, such as a new assemblage that evinces her longstanding interest in children’s toys and development. (It incorporates the classic wood and wire plaything known as a bead maze).

Her exhibition opens up new ways of looking at familiar postwar art, particularly with respect to the repetition and seriality used by many Minimal and Conceptual artists; we are invited to think about how these strategies relate to the experience of neurodiversity. As Barrada says, “Deligny conceives of autism not as a pathology, but as another way of being in the world.”