Chicago’s Kavi Gupta gallery, founded in 2000, has been ahead of the curve in bringing exposure to emerging BIPOC artists as well as artists with long careers who had been unjustly overlooked. Among the contemporary art stars it nurtured with early-career exhibitions are Jeffrey Gibson and Angel Otero; also on the roster are Jae Jarrell, Deborah Kass, and Beverly Fishman, women who have been working steadily for decades and are just now getting their due. The gallery has also been a pioneer in Chicago’s West Loop neighborhood, arriving before the area transformed into a post-industrial playground akin to the meatpacking district in New York City.

In addition to supporting artists through the gallery, founder Kavi Gupta and his wife Jessica Moss (who is the gallery’s principal and was previously the curator of contemporary art at the University of Chicago’s Smart Museum of Art) both come from philanthropic, art-collecting families and have amassed an extensive private collection together. In a recent virtual event, organized by Artful in conjunction with Independent Curators International on the occasion of the art fair EXPO Chicago, Gupta and his Director of Exhibitions David Mitchell gave a tour of the works currently installed in Moss and Gupta’s apartment atop their gallery in the West Loop.

The quotes below have been edited and condensed from Artful’s “Artful Anywhere” virtual event on April 10, 2021, conducted by Artful’s co-founder and chief curator Matthew Israel.

Angel Otero, Everything and Nothing, 2011. Also pictured: Devan Shimoyama, Tamir VI, 2019 (left).

Kavi Gupta: We have worked with Angel since his days at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. This monumental piece came from our first exhibition with him. I found it to be one of the masterpieces of that show—I had to have it. He’s layering hundreds of oilskins to make these surfaces.

David Mitchell: Angel’s really an innovator. The surface of the painting is very sculptural. He’s painting glass with oil, which he’s then peeling up as an enormous sheet and draping over the canvas. That creates these big, beautiful, expressive drapery passages, which also allow him to show the underside of a painting. You’re actually seeing a painting from the inside out.

Manish Nai, Untitled, 2017

KG: Manish, who is from India, is somebody I have been following closely—I really believe in his practice, which comes out of social, political, and economic issues. He comes from a poor background and is looking at the poor castes in India, using materials that come from India and exploring the history of the country’s dichotomy of wealth and poverty.

This piece is made from molded jute dyed with indigo. Indigo has a long history; during the British Raj period, it became a huge commodity for export. Farmlands were converted to indigo fields, and there were fewer vegetable crops. At some point the Germans developed a way to synthesize indigo, and it took that whole market away from India. Subsequently it was found that aggressive indigo farming would poison the ground and vegetation—the farming could not come back for many many years, and it still is a factor in the famine that exists today.

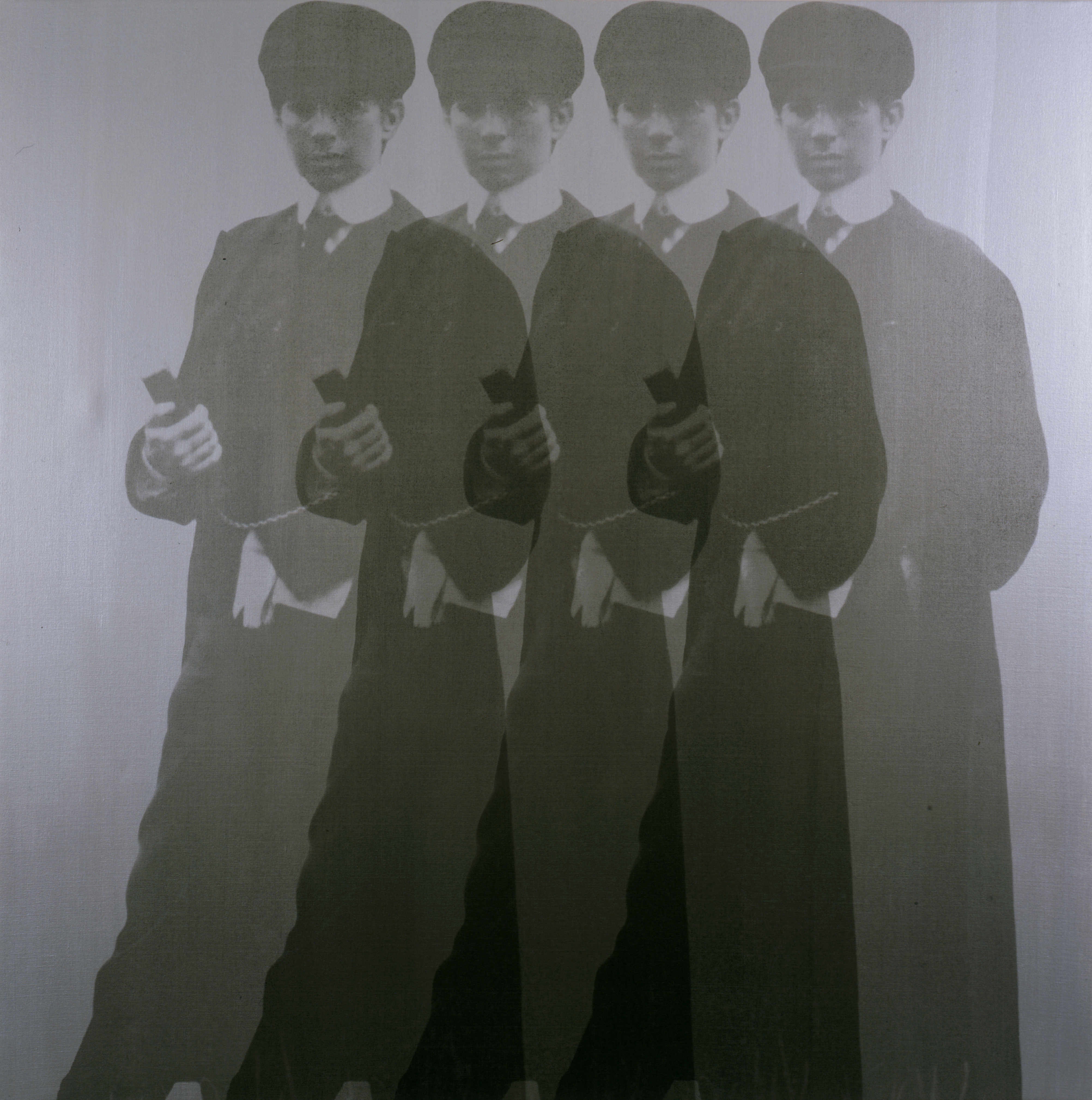

Deborah Kass, Quadruple Yentl (My Elvis), 1997

DM: Deborah Kass is known for the appropriation of imagery. In 1990 she became especially well-known for doing emulations of Warhol. This is a piece based on Warhol’s “Silver Elvis” works, but rather than having Elvis as a cowboy and icon of American masculinity she’s used an image of Barbra Streisand in the film Yentl. Deborah Kass is a lesbian; she’s also Jewish, and Yentl is this iconic film featuring a Jewish woman in a sort of gender-ambiguous role where she is entering a yeshiva, or Jewish religious school, as a woman dressed as a man. It became the perfect means of subverting this violent masculinity of Elvis as a cowboy, leveraging also Warhol's iconic style.

KG: Deb is an artist we recently started to work with—we thought she was really underappreciated for how important she was in the ‘80s, as part of the school that was looking at Warhol and using appropriation to deal with gender issues.

Hans Hofmann, Blissful Darkness, 1959.

KG: Our families have been multigenerational collectors, and we serve as custodians to a few of the great modernist pieces in our family collections. One of the most significant is this 1959 painting by Hans Hofmann.

DM: Hofmann was a teacher, speaker, and writer, and one of the only male Abstract Expressionist artists who was willing to be in dialogue with and champion women artists. This legacy of artists uplifting other artists is really crucial to the collection.

Roger Brown, A Visit To A Small Italian City, 1991

KG: We are fortunate to have taken on the Roger Brown estate, one of the artists I did my undergrad dissertation on. He was one of the Chicago Imagists, and an artist who had been forgotten and needs much more recognition. He dealt with politics, sexuality, all of these issues that were not discussed in art in the ‘80s.

DM: The Imagists have been really crucial to the rise of figuration in the past few years. They were enormously influential in terms of their willingness to draw inspiration from all of these different modes of production, like comic books and folk art, as well as their political take on figuration.

Mickalene Thomas, Brawlin’ Spitfire Wrestlers, 2008, and The Magic of Believing, 2014. Also pictured: Andy Warhol, Brillo Pouf.

KG: Mickalene is a first mover in so many ways, an artist who opened the door for so many other female, black, queer artists. This sculpture is one of her earliest pieces, of female wrestlers made out of porcelain but using her signature crystals. She is playing with the beauty of these characters, but also the pain and struggle that they’re going through as women.

The painting was part of our first exhibition with Mickalene, an immersive, substantial exhibition in 2014 which won an award from the Art Critics Association for the best gallery exhibition in the country at that time. It was prepared following her mother's passing and she had produced a documentary film about her mother, Happy Birthday to a Beautiful Woman, which aired on HBO. She had re-created her mother’s basement in the gallery, and she had bronzed all of her mother’s most important possessions as a way to memorialize them. And she did a series of paintings of sayings that her mother was using as she was passing as a way to console herself. This one says “The magic of believing” and is surrounded by an ensō, or Buddhist circle.

Jessica Stockholder, Catapult Anime Stack, 2015

-1-300.jpg) KG: Jessica is one of the most significant artists living today. She freed up artists to define sculpture any way they wanted to. After teaching at Yale for fifteen years she moved to Chicago, and we did an immersive two-gallery exhibition with her which took over the inside and outside of the buildings. This is one of the pieces from that show.

KG: Jessica is one of the most significant artists living today. She freed up artists to define sculpture any way they wanted to. After teaching at Yale for fifteen years she moved to Chicago, and we did an immersive two-gallery exhibition with her which took over the inside and outside of the buildings. This is one of the pieces from that show.

DM: The question of how art is displayed is something she’s always examining in really dynamic ways. This is sort of an assemblage of objects that she put on top of a pedestal, and the pedestal itself is supported by another found object cut from furniture. So there’s a sculpture supporting a pedestal supporting sculpture.

Jack Whitten, Soulspace X (Black Jasmine), 1984 (on back wall). Also pictured: works by Jae Jarrell (on mannequin), Glenn Ligon (top), and Kerry James Marshall (bottom).

KG: This is a really early find of mine, a Jack Whitten from the early ‘80s. We discovered after doing some research on it that there was a tag on it that said “Collection Geldzahler,” which goes back thirty years. I find it so important that Henry Geldzahler, one of the preeminent curators of his time and a definer of numerous movements, was collecting Black abstract artists when no one else was looking at those artists. For me, it represents a profound moment about what needed to happen in the art world.

KG: This is a really early find of mine, a Jack Whitten from the early ‘80s. We discovered after doing some research on it that there was a tag on it that said “Collection Geldzahler,” which goes back thirty years. I find it so important that Henry Geldzahler, one of the preeminent curators of his time and a definer of numerous movements, was collecting Black abstract artists when no one else was looking at those artists. For me, it represents a profound moment about what needed to happen in the art world.

Jeffrey Gibson, Radiant Tushka, 2018

KG: We just got this amazing Jeffrey Gibson piece back from two years of loans to various museums. Jeffrey is an artist we started working with early, when he did not have gallery representation. He was somebody that I believed in and followed for many years. His background is quite significant and pertains to much of what the gallery is about. The gallery has really developed a reputation for finding new artists doing various types of social practices that were really unheard of early on, and now have gone on to stardom.

KG: We just got this amazing Jeffrey Gibson piece back from two years of loans to various museums. Jeffrey is an artist we started working with early, when he did not have gallery representation. He was somebody that I believed in and followed for many years. His background is quite significant and pertains to much of what the gallery is about. The gallery has really developed a reputation for finding new artists doing various types of social practices that were really unheard of early on, and now have gone on to stardom.

DM: Jeffrey is Choctaw-Cherokee, but he didn’t really grow up strictly as part of a Native American community. He grew up around the world, partly in South Korea and partly in Germany, and traveling all around influenced his work. He has this optimistic vision of the world as a collective community, and he feels that some of the art forms that are a part of his culture and family history are uplifting and can integrate with the togetherness that he found within music communities around the world.

Beverly Fishman, Untitled, 2017 (above sofa). Also pictured: works by Wadsworth Jarrell (left) and Marc Swanson (on table).

KG: Beverly, who is in her mid-sixties, was the head of the Cranbrook Academy of Art and just left after years of teaching there. This work employs her research in the pharmaceutical industry—she has studied how prescription drugs have become a pervasive force in contemporary culture.

KG: Beverly, who is in her mid-sixties, was the head of the Cranbrook Academy of Art and just left after years of teaching there. This work employs her research in the pharmaceutical industry—she has studied how prescription drugs have become a pervasive force in contemporary culture.

DM: She’s also playing with art history, finding this intersection between these super-masculine abstract painters of the fifties, sixties, seventies and thinking about how the language those artists used to describe the uplifting potential of the artwork is the same kind of language the pharmaceutical companies used to describe the uplifting potential of medications.

Adrian Piper, What’s It’s Like, What It Is #2.1, 1991

KG: This is an important piece in the collection, and one I bought very early. It’s an Adrian Piper cutout, from a series of works that she had shown at the Guggenheim in 1991 called “What It's Like, What It Is,” which dealt with racial injustice in this country. This specific piece depicts the lawyers coming out of the trial for the Howard Beach murders in Queens, where a group of white men were convicted of murdering a Black man for being in a white neighborhood. The lawyers were able to get that white man off, and the source image for this work shows them leaving the courthouse. This picture was on the front page of the newspapers. You can feel the grotesqueness of it. To me, it’s a powerful, powerful statement.

KG: This is an important piece in the collection, and one I bought very early. It’s an Adrian Piper cutout, from a series of works that she had shown at the Guggenheim in 1991 called “What It's Like, What It Is,” which dealt with racial injustice in this country. This specific piece depicts the lawyers coming out of the trial for the Howard Beach murders in Queens, where a group of white men were convicted of murdering a Black man for being in a white neighborhood. The lawyers were able to get that white man off, and the source image for this work shows them leaving the courthouse. This picture was on the front page of the newspapers. You can feel the grotesqueness of it. To me, it’s a powerful, powerful statement.