New York’s alternative art spaces, many of which date from the SoHo loft scene of the 1970s, play an undersung behind-the-scenes role in an art world that often seems, from the outside, to be powered by the movements and machinations of commercial galleries. The city’s oldest one, White Columns—founded in 1970 as 112 Greene Street by artists Gordon Matta-Clark and Jeffrey Lew—gave crucial early shows to now-canonical artists including Cady Noland, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and Chris Burden. During the AIDS crisis of the 1980s, it offered artist-activist groups such as ACT UP an essential outlet; more recently, under director and chief curator Matthew Higgs, it has reliably championed artists with developmental disabilities and persuaded museum curators to take notice.

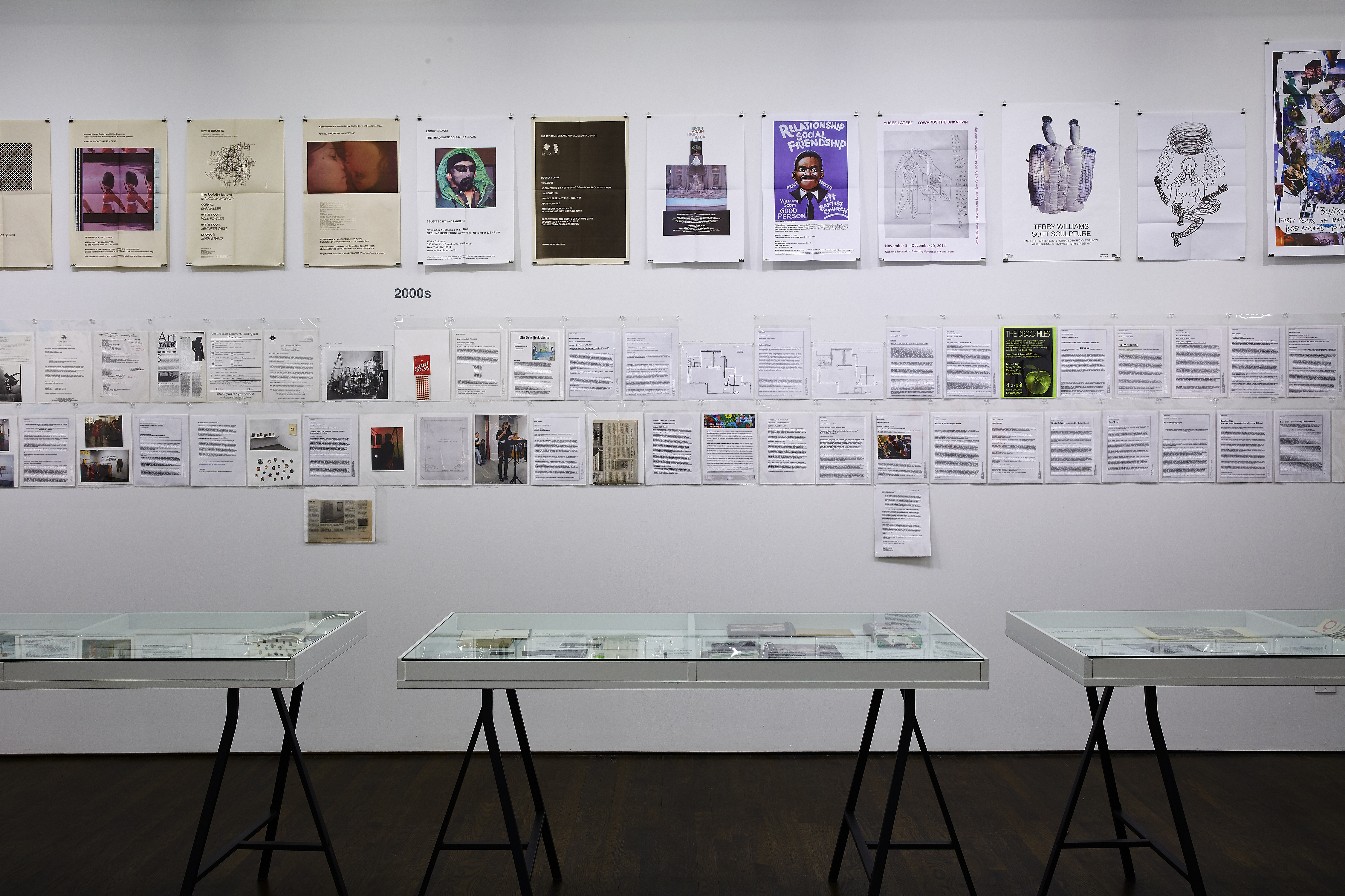

White Columns, currently located on Horatio Street in the West Village not far from the Whitney Museum, is now marking its 50th anniversary with the exhibition “From the Archives: White Columns and 112 Greene Street—1970-2021” (through July 31). With documentary photographs and all sorts of ephemera, it delves into some of the important moments in the space’s history and is, especially in this post-pandemic period, a celebration of sheer endurance.

In an interview with Artful’s Editorial Director Karen Rosenberg, Higgs spoke about the many lives of White Columns/112 Greene Street over the years, the strategies that enabled it to survive 2020, and why alternative spaces matter more than ever in a world of social media, fairs, and mega-galleries.

Karen Rosenberg: To start off, can you tell me a little about the show and how it’s organized?

Matthew Higgs: It’s structured as a timeline, with a lot of printed materials and photographic records of what happened at 112 Greene Street and then from 1980 onwards at White Columns. And it’s really an attempt to sort of plot, represent, and articulate the history of these spaces.

The show focuses on things that we might now consider historically significant. We have twenty separate vitrines in the exhibition, and each one focuses on something important that took place at 112 Greene Street or White Columns. For example, there are materials relating to Louise Bourgeois’s quite significant exhibition from 1974, which was her first show in New York in more than a decade. Another one of the vitrines relates to Elaine Sturtevant’s comeback exhibition in 1986, and another is Fred Wilson’s 1990 project “The Other Museum,” and so on.

How has the space evolved over the years?

The 1970s, at 112 Greene Street, were very much a time of installation, performance, and dance. There’s also an interesting intersection between the literary world and the downtown visual arts scene, so there were a lot of readings as well. It’s quite experimental. But even though the space seemed very underground and informal, the first show was reviewed by Peter Schjeldahl in The New York Times. From the outset, people paid attention to what was unfolding at 112 Greene Street. And there was a whole subsequent explosion of alternative art spaces in New York, like Artists Space and The Kitchen, which were founded in the early ‘70s.

In 1980 the space moved to 325 Spring Street, and Josh Baer became the director and changed the name to White Columns. During his tenure, the late ‘70s into the early ‘80s, the program moved away from the experimental, free-form work associated with 112 Greene Street. It became much more exhibition-based.

Each time a new director takes over, they put their fingerprints on the program. When Bill Arning arrived, things started to become more politicized. In ‘87 Group Material did a big project. In 1988 he gave the space to ACT UP and they made one of their earliest gallery interventions. The character of White Columns changed again in the ‘90s when Paul Ha was in charge, and you started to see the development of thematic group shows. I arrived in 2005 and you’ve been witness to a lot of my tenure here, including our support for artists with disabilities.

As much as the organization is about the different directors at any given time, it’s about the collective effort of literally thousands of artists and hundreds of other people. The exhibition is also about the context we share with our peer organizations, places like Artists Space and The Kitchen—how they have functioned as incubators and experimental platforms, operating outside of the commercial markets and larger institutional forces. And how perhaps in New York, which is fortunate to still have many of these organizations, this idea of an alternative art space still seems relevant.

.jpg)

As the space has evolved, so has the larger ecosystem around it. The art world is so much bigger and more global than it was when 112 Greene Street was founded, and the discovery system for artists is now heavily influenced by fairs, social media, and mega-galleries. How do White Columns and other alternative spaces fit into all of this?

Historically, a space like White Columns was where you would have your first encounter with an artist’s work. That was really true in the 1970s; it’s certainly true in the 1980s and after. Since I’ve been here, the art world has expanded; it’s recently contracted a little but during the last twenty years it has expanded extraordinarily. It’s interesting to look at the late ‘80s, when Bill Arning was writing about this issue—saying, why do we need White Columns, when there’s a burgeoning scene in Soho and there’s a burgeoning scene in the East Village? I think it always comes back to this idea that we are fundamentally interested in artists before any kind of consensus forms around their work. Typically when we show an artist, there isn’t much of a narrative in terms of critical, commercial, or curatorial support. Those things might come later.

A lot of the artists we support don’t have conventional arts education or training. One of the things that we hope has been successful in the program has been the mix of emerging artists, older artists, artists with unconventional training, and artists with disabilities—allowing all of that work to coexist without making any clear or obvious distinctions.

When we started supporting artists with developmental disabilities fifteen years ago, I don’t think a lot of people picked up on it. But now, we’re starting to see a much greater, wider, more sophisticated interest from other places. For example, we gave William Scott his first solo show in 2006, and works of his recently entered the Museum of Modern Art’s collection.

You are the oldest alternative space in the city. What do you think has been the secret to your survival?

It’s about the continued reinvention and reimagining of the space. What I think you find in the history of White Columns and 112 Greene Street is that the idea is constantly in flux, and informed by artists. A lot of the great conversations we’ve had that become exhibitions start with conversations with artists who introduce us to other artists.

A great example would be Bill Arning’s tenure in the late 80s when the work becomes very political and we start to see the emergence of groups like ACT UP, the Stonewall 25th anniversary exhibition, the practices of Group Material or Felix Gonzalez-Torres. You start to see a shift informed by artists’ concerns. I think the reason all these organizations have survived in New York is that they’ve been very responsive to artists. Also the wider art community in New York City understands the value of these organizations and the continued relevance of them, which is how we have survived.

All of that said, this past year and a half has been a really tough period for all art spaces. What were some of the things that you did to get through it? Were you ever worried, at any point, that this might be the end?

If you spend any time with this organization’s finances, you know that it has never had a good year in fifty years! It’s always struggled financially. And that struggle is reflected in the spirit of the space and, often, the kind of work that the space was in a position to support. But the last eighteen months have been really interesting. We came together with our peer organizations, about fifteen of us, to form a coalition—we fund-raised together and applied together to some of the larger foundations, and really just made the case that these spaces are important. They are important now, they were important in the past and they’ll continue to be important in the future.

We all have relatively modest budgets and staffing. Almost none of us charge for admission. So the absent audience during the pandemic wasn’t really the primary concern. What was a concern, though, was making sure that these organizations could support their staff and maintain their spaces, and would be ready to reopen when we were able to do so. That collective effort was incredibly successful from both a financial perspective and a culture and community perspective—we had a real opportunity to talk and work together and find our common interests, while also at the same time underscoring to potential funders the differences between, say, the Swiss Institute and Recess.

And then Hauser & Wirth made an extraordinary philanthropic gesture in September, when they organized a selling exhibition, “Artists For New York.” The beneficiaries included larger organizations like the New Museum and Dia and the Studio Museum in Harlem, but also smaller ones like White Columns.

.jpg)

What are you seeing as the city enters a new post-pandemic phase? How are you and other alternative spaces planning for this uncertain future?

We reopened in September. Foot traffic in galleries has been dropping off for a decade, and things are definitely quieter. There’s no really clear sense of when we’ll get back to normal, if we ever get back to normal. But we certainly don’t face the same challenges as larger museums that have had to lay off staff and cut back budgets. White Columns has a staff of four people, including me, and of all of the organizations in our peer coalition we had the smallest budget.

Going forward, it’s a question of whether philanthropy functions in the same way. We had planned a 50th-anniversary gala, which was planned to take place in March 2021, but we had to cancel that. We’re thinking about whether we’ll reschedule that for some point in the future as an historical celebration of the organization and bring back a lot of the people who were instrumental in the early days. We also canceled two in-person benefit auctions, in 2020 and 2021, which normally provide us with a significant amount of our budget. It’s been complicated, but there are very deep traditions in New York of support for organizations like ours. My guess is that that sort of cultural philanthropy will continue.

What do you think “alternative space” means in 2021, compared to in 1970 when 112 Greene Street was founded?

Jeffrey Lew’s initial philosophy was that there would be no hierarchy of any kind. His idea, which was actually quite radical, was to create a space where established artists and unknown artists could show alongside each other. That changed in the ‘90s, when White Columns became in people’s imagination a space where completely unknown artists show at the beginning of their careers—one that functioned as a feeder to the commercial art world. I don’t think that was ever really the intention, but it became a perception.

We don’t represent artists. One of the great things about this exhibition is just that so many artists have shown here, because artists only show here once and then they move on. A commercial gallery has its program of twenty artists and they work with that program over decades. Here there’s just this constant renewal of energy and ideas, which is dictated and driven by whatever’s coming into the space next.

By the time I got here in the early 2000’s, the art world had expanded dramatically—not just in New York but nationally and internationally, assisted by technology networks and also the rise of art fairs. I saw an opportunity to think about what wasn’t being addressed, and whether we could address it at White Columns in a meaningful and intelligent way. That’s when we began our support of artists with disabilities, because almost no contemporary art spaces anywhere were showing that work. As of today we’ve organized twenty-five solo shows with artists with disabilities and up to forty projects in total, working with organizations that support artists with disabilities nationally.

Certainly in the last two or three years we’ve seen the art world struggling to create a more diverse, representative and equitable idea of art, but alternative spaces have been working on these projects in different ways, with different communities, for a very long time.

As you prepared for this show and went digging through the archives, did you come across anything that surprised you?

The exhibition history I was fairly familiar with. But there are still artists who emerged from the research process for this show who seem completely fascinating to me but have somehow slipped through the net. I’m looking at one now, Paula Longendyke, and all we have from her 1975 show is the invitation card and a review from Artforum. The review makes this artist’s work sound incredible to me, and reminds me that there’s a lot more research to be done. The critic, Alan Moore, describes 112 Greene Street’s aesthetics as “formal funk”—I think that’s quite a nice way to think about the organization in that period, when punk rock is just around the corner. You start to see that sort of sensibility becoming much more present in the program.

I also hadn’t known that Chris Burden did his first-ever performance in New York at 112 Greene Street in 1974. We have great documentation of him laying on a table shirtless with a sign above that says “Please push pins into my body”—rather like Yoko Ono’s earlier Cut Piece.

Another interesting finding from the archives was the price lists for various exhibitions. I think people are always thinking of alternative spaces with a kind of disregard for economic necessities. From the very beginning, though, artists wanted their work to be available for sale. We still have quite a lot of the price lists, and some of them are really interesting.

Susan Rothenberg had her first show here in 1975, when she showed her horse paintings for the first time. It’s a significant moment in the organization’s history, because it wasn’t really known for showing painting. When she died last year Peter Schjeldahl wrote a great piece in The New Yorker, and said that these works were a visceral shock to the New York art world because they really preempt the Neo-Expressionist painting of the late ‘70s and early ‘80s by five years. We found a price list for that show, and the paintings were priced at $5,000, which would have been a lot of money at the time. But then, in 1988 when Felix Gonzalez-Torres shows here, he shows Perfect Lovers, the piece with the two clocks next to each other. It was installed above Bill Arning’s desk in the office, and priced at $350.

.jpg)

What are some other alternative spaces that inspire you, or new developments in that area?

What I’ve noticed in the last twenty years is that there are fewer new spaces starting up. I think a lot of this has to do with the lure of the commercial art world and the way it became internationalized—people who might have gravitated to opening a nonprofit or independent artist-run space have instead opened boutique commercial spaces. Technology and social media have also allowed people to create platforms for themselves and others in a way that negates the need for physical space.

In London in the early ‘90s, for example, there were plenty of artist-run spaces. There are fewer now and I think a lot of that energy went into the forming of collectives, as we’re seeing with the recent Turner Prize nominations. I think the idea of an artists’ collective is perhaps more compelling now than an artists’ space, simply because you can organize on social media and without the burden of real estate.

If anything good comes out of the pandemic in New York, it would be rent relief that would allow a new generation to start thinking about physical space, real encounters with work, and creating social networks in person. We’ve seen a lot of the art world gravitate to Tribeca recently, which would have been inconceivable three or four years ago because of the rents.

I’m old-school—I think one of the things this exhibition shows you is that the relationship between real estate and ideas, at any given point in time, is often quite profound. The spaces that White Columns occupied were also, I think, instrumental in shaping the program and the work that was done. Now we find ourselves in the middle of a meatpacking district that’s continuing to undergo dramatic changes with the arrival of Little Island and David Hammons’s pier. These are two things which seem to be fundamentally at odds with each other, but they’re both part of a narrative that begins with artists occupying those piers in the ‘70s and sowing the seeds of ideas.

The Hammons piece on Pier 52, Day’s End, seems particularly relevant to the history of White Columns. It’s a tribute to a 1975 project made on that site by Gordon Matta-Clark, who co-founded 112 Greene Street with Jeffrey Lew.

It’s great that the Whitney and David Hammons built that project at the end of our street, because we can sort of piggyback onto the celebration of Matta-Clark’s work and spirit, which permeated 112 Greene Street. The atmosphere and attitude of his work is really present in all of the programming through the 70s, even though he wasn’t directing the space as such.

The idea of the historical versus the present is something that I hope resonates in the exhibition. One thing I noticed when we were installing the show is that a lot of the printed invitations or press releases, especially from the ‘70s and ‘80s, don’t include the year. You’ll find a piece of cardboard that will say February to March but it won’t tell you that it’s 1974, and I think it’s because they weren’t thinking historically about the work they were doing in the moment. That push-pull between the present and history is really what the exhibition’s about, trying to encourage people to think about Gordon Matta-Clark in the 1970s and then thinking about what our relationship with his work is now.